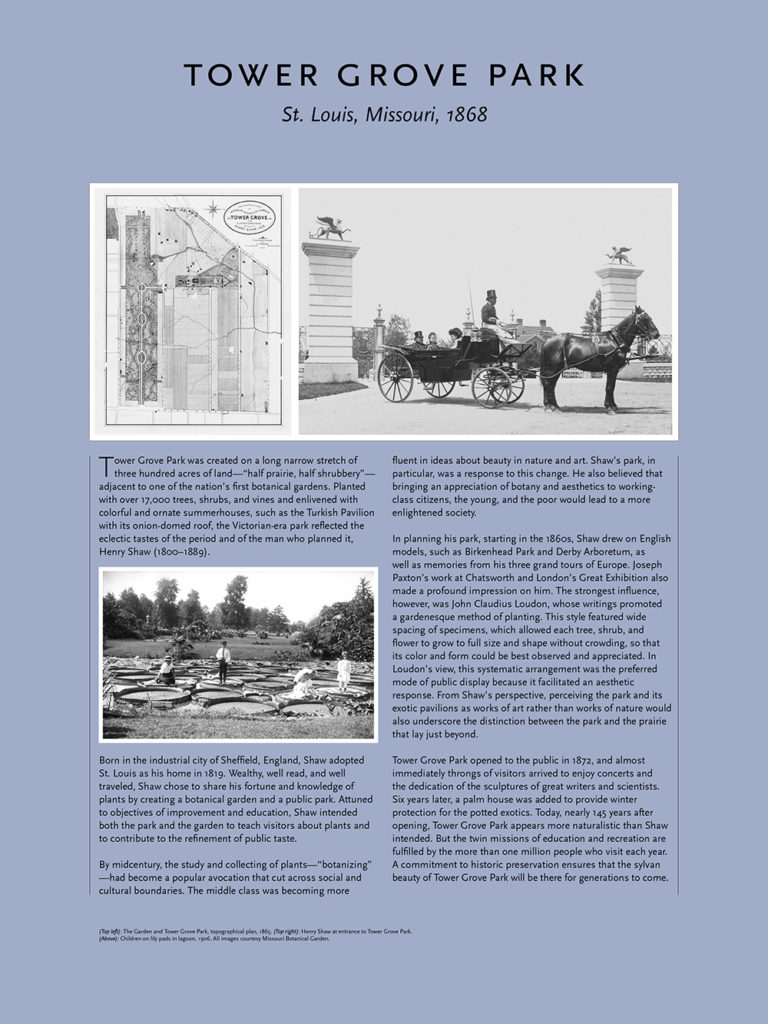

Tower Grove Park was created on a long narrow stretch of three hundred acres of land—“half prairie, half shrubbery”—adjacent to one of the nation’s first botanical gardens. Planted with over 17,000 trees, shrubs, and vines and enlivened with colorful and ornate summerhouses, such as the Turkish Pavilion with its onion-domed roof, the Victorian-era park reflected the eclectic tastes of the period and of the man who planned it, Henry Shaw (1800–1889).

Born in the industrial city of Sheffield, England, Shaw adopted St. Louis as his home in 1819. Wealthy, well read, and well traveled, Shaw chose to share his fortune and knowledge of plants by creating a botanical garden and a public park. Attuned to objectives of improvement and education, Shaw intended both the park and the garden to teach visitors about plants and to contribute to the refinement of public taste.

By midcentury, the study and collecting of plants—“botanizing”—had become a popular avocation that cut across social and cultural boundaries. The middle class was becoming more fluent in ideas about beauty in nature and art. Shaw’s park, in particular, was a response to this change. He also believed that bringing an appreciation of botany and aesthetics to working-class citizens, the young, and the poor would lead to a more enlightened society.

In planning his park, starting in the 1860s, Shaw drew on English models, such as Birkenhead Park and Derby Arboretum, as well as memories from his three grand tours of Europe. Joseph Paxton’s work at Chatsworth and London’s Great Exhibition also made a profound impression on him. The strongest influence, however, was John Claudius Loudon, whose writings promoted a gardenesque method of planting. This style featured wide spacing of specimens, which allowed each tree, shrub, and flower to grow to full size and shape without crowding, so that its color and form could be best observed and appreciated. In Loudon’s view, this systematic arrangement was the preferred mode of public display because it facilitated an aesthetic response. From Shaw’s perspective, perceiving the park and its exotic pavilions as works of art rather than works of nature would also underscore the distinction between the park and the prairie that lay just beyond.

Tower Grove Park opened to the public in 1872, and almost immediately throngs of visitors arrived to enjoy concerts and the dedication of the sculptures of great writers and scientists. Six years later, a palm house was added to provide winter protection for the potted exotics. Today, nearly 145 years after opening, Tower Grove Park appears more naturalistic than Shaw intended. But the twin missions of education and recreation are fulfilled by the more than one million people who visit each year.

For more on Tower Grove Park read Henry Shaw’s Victorian Landscapes: the Missouri Botanical Garden and Tower Grove Park by Carol Grove.