During the first decade of the twentieth century, Hugh Landon and Linnaes Boyd, executives of the Indianapolis Water Company, scouted locations for a reservoir along a branch of a defunct canal system northwest of the city. Although the reservoir was never built, the men purchased fifty-two acres along the bluffs of the White River and divided the land into roughly equal parcels. Boyd subdivided his twenty-six acres, while Landon embarked on building an estate that he called Oldfields.

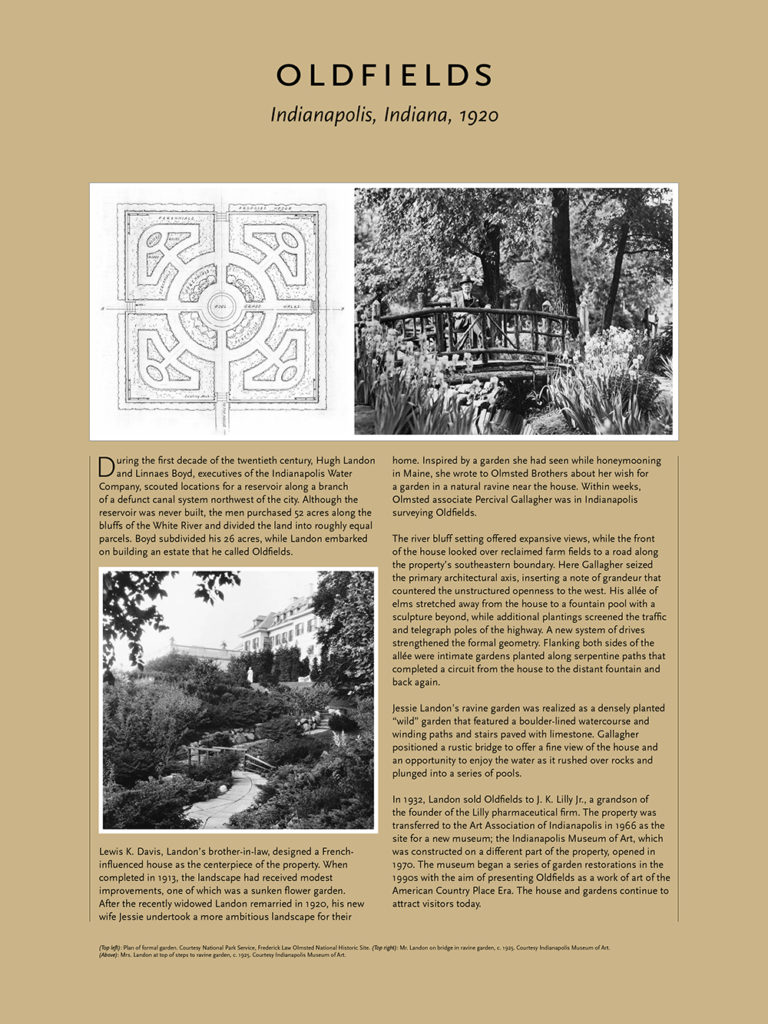

Lewis K. Davis, Landon’s brother-in-law, designed a French-influenced house as the centerpiece of the property. When completed in 1913, the landscape had received modest improvements, one of which was a sunken flower garden. After the recently widowed Landon remarried in 1920, his new wife Jessie undertook a more ambitious landscape for their home. Inspired by a garden she had seen while honeymooning in Maine, she wrote to Olmsted Brothers about her wish for a garden in a natural ravine near the house. Within weeks, Olmsted associate Percival Gallagher was in Indianapolis surveying Oldfields. He quickly created the garden’s basic structure, but saw potential beyond this single garden and recommended a more extensive landscape treatment.

The river bluff setting offered expansive views, while the front of the house looked over reclaimed farm fields to a road along the property’s southeastern boundary. Here Gallagher seized the primary architectural axis, inserting a note of grandeur that countered the unstructured openness to the west. His allée of elms stretched away from the house to a fountain pool with a sculpture beyond, while additional plantings screened the traffic and telegraph poles of the highway. A new system of drives strengthened the formal geometry. Flanking both sides of the allée were intimate gardens planted along serpentine paths that completed a circuit from the house to the distant fountain and back again. Additional features included an estate wall with decorative iron gates and a productive orchard.

Jessie Landon’s ravine garden was realized as a densely planted “wild” garden that featured a boulder-lined watercourse and winding paths and stairs paved with limestone. Gallagher positioned a rustic bridge to offer a fine view of the house and an opportunity to enjoy the water as it rushed over rocks and plunged into a series of pools.

In 1932, Landon sold Oldfields to J. K. Lilly Jr., a grandson of the founder of the Lilly pharmaceutical firm. Although the Lillys undertook improvements of their own, they left Gallagher’s work largely unchanged. The property was transferred to the Art Association of Indianapolis in 1966 as the site for a new museum; the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which had been constructed on a different part of the property, opened in 1970. The museum began a series of garden restorations in the 1990s with the aim of presenting Oldfields as a work of art of the American Country Place Era. The house and gardens continue to attract visitors today.