By the turn of the eighteenth century, Vermont retained little of the forestland that once covered the state. Sheep farming had led to clear-cutting that produced soil-depleted slopes and silt-choked streams. One of the keenest observers of man’s misuse of this landscape was George Perkins Marsh, born in the small town of Woodstock in 1801. The inquisitive, gifted boy grew to become a lawyer, a congressman, and, eventually, a diplomat. In 1864, Marsh wrote Man and Nature, a book that warned of the dire effects of deforestation, effectively laying out the conceptual foundations of the American conservation movement.

Among those deeply influenced by Marsh’s book was another resident of Woodstock, Frederick Billings (1823-1890), a prosperous businessman who grew up in view of the Marsh mansion. When gold was discovered in California in 1849, Billings left Vermont to seek his fortune, and he made it quickly. Confronted with the grandeur of Yosemite Valley, he fell in love with the sublime scenery of the West.

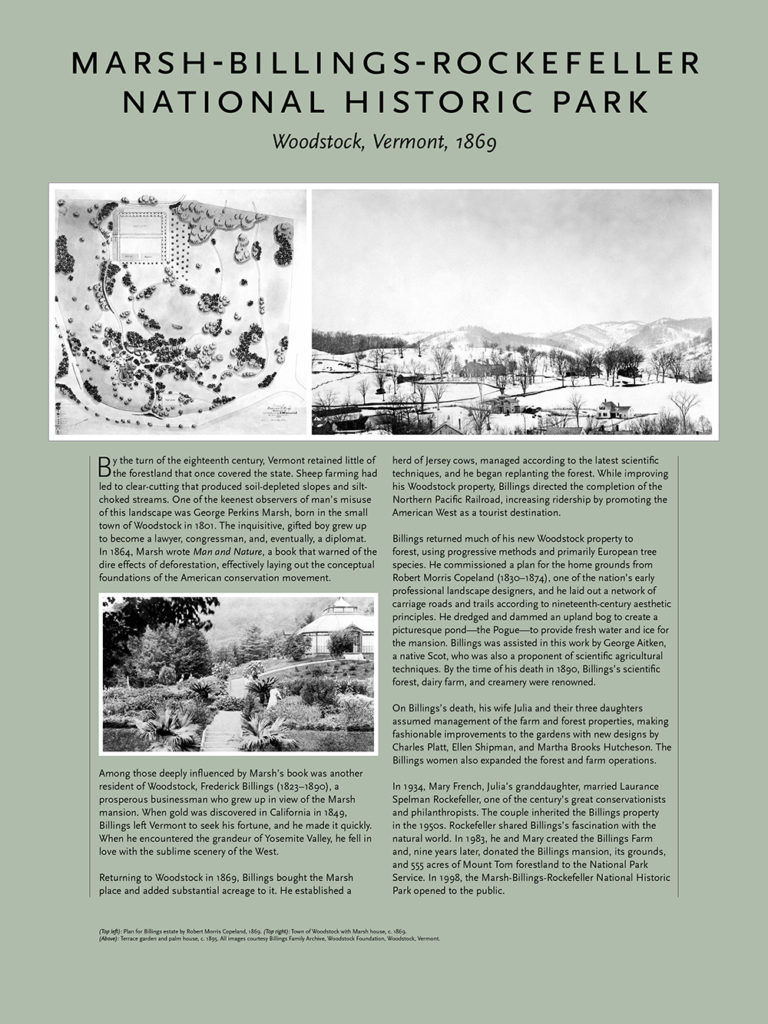

Returning to Woodstock in 1869, Billings bought the Marsh place and added substantial acreage to it. He established a herd of Jersey cows, managed according to the latest scientific techniques, and began replanting the forest. While improving his Woodstock property, Billings directed the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad, increasing ridership by promoting the American West as a tourist destination.

Billings returned much of his new Woodstock property to forest, using progressive methods and primarily European tree species. He commissioned a plan for the home grounds from Robert Morris Copeland (1830-1874), one of the nation’s early professional landscape designers, who laid out a network of carriage roads and trails according to nineteenth-century aesthetic principles. He dredged and dammed an upland bog to create a picturesque pond–the Pogue–to provide fresh water and ice for the mansion inhabitants. Billings was assisted in this work by George Aitken, a native Scot, who was also a proponent of scientific agricultural techniques. By the time of his death in 1890, Billing’s scientific forest, dairy farm, and creamery were renowned.

On Billing’s death, his wife Julia and their three daughters assumed management of the farm and forest properties, making fashionable improvements to the gardens with new designs by Charles Platt, Ellen Shipman, and Martha Brooks Hutcheson. The Billings women also expanded the forest and farm operations.

In 1934 Mary French, Julia’s granddaughter, married Laurance Spelman Rockefeller, one of the century’s great conservationists and philanthropists. The couple inherited the Billings property in the 1950s. Rockefeller shared Billings’s fascination with the natural world. In 1983 he and Mary created the Billings Farm and nine years later, donated the Billings mansion, its grounds, and 555 acres of Mount Tom forestland to the National Park Service. In 1998 the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Park opened to the public.