In spring 1858, Frederick Law Olmsted met Calvert Vaux at his Manhattan office to divide the $2,000 fee they had earned after winning the Central Park design competition. At the time, Vaux told his friend that after the park was done they could “carry on the business that it would inevitably lead to.” Vaux’s prediction proved true—many communities sought out the partners to emulate America’s first great municipal pleasure ground. One of them was the growing city of Buffalo, at the western terminus of the Erie Canal.

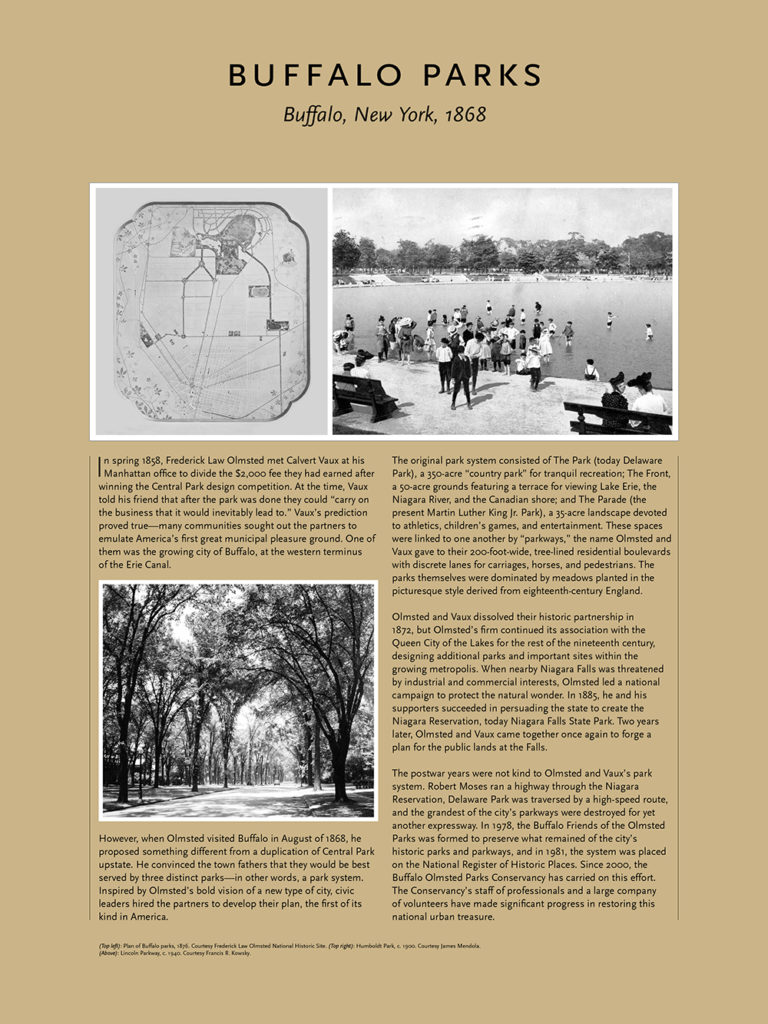

However, when Olmsted visited Buffalo in August of 1868, he proposed something different from a duplication of Central Park upstate. He convinced the town fathers that they would be best served by three distinct parks—in other words, a park system. Inspired by Olmsted’s bold vision of a new type of city, civic leaders hired the partners to develop their plan, the first of its kind in America.

The original park system consisted of The Park (today Delaware Park), a 350-acre “country park” for tranquil recreation; The Front, a 50-acre grounds featuring a terrace for viewing Lake Erie, the Niagara River, and the Canadian shore; and The Parade (the present Martin Luther King Jr. Park), a 35-acre landscape devoted to athletics, children’s games, and entertainment. These spaces were linked to one another by “parkways,” the name Olmsted and Vaux gave to their 200-foot-wide, tree-lined residential boulevards with discrete lanes for carriages, horses, and pedestrians. The parks themselves were dominated by meadows planted in the picturesque style derived from eighteenth-century England.

Olmsted and Vaux dissolved their historic partnership in 1872, but Olmsted’s firm continued its association with the Queen City of the Lakes for the rest of the nineteenth century, designing additional parks and important sites within the growing metropolis. When nearby Niagara Falls was threatened by industrial and commercial interests, Olmsted led a national campaign to protect the natural wonder. In 1885, he and his supporters succeeded in persuading the state to create the Niagara Reservation, today Niagara Falls State Park. Two years later, Olmsted and Vaux came together once again to forge a plan for the public lands at the Falls.

The postwar years were not kind to Olmsted and Vaux’s park system. Robert Moses ran a highway through the Niagara Reservation, Delaware Park was traversed by a high-speed route, and the grandest of the city’s parkways were destroyed for yet another expressway. In 1978, the Buffalo Friends of the Olmsted Parks was formed to preserve what remained of the city’s historic parks and parkways, and in 1981, the system was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Since 2000, the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy has carried on this effort. The Conservancy’s staff of professionals and a large company of volunteers have made significant progress in restoring this national urban treasure.

For more on the Buffalo parks read The Best Planned City in the World: Olmsted, Vaux, and the Buffalo Park System by Francis R. Kowsky or watch The Best Planned City in the World.

For more about Frederick Law Olmsted read Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England.