Tupper Thomas, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York (2011)

In 1980, Tupper Thomas was a young mother in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood. After spending several years at home raising her children, she spotted an ad in the New York Times for the position of Prospect Park administrator. “I thought, ‘How lovely—if I got this job, I would live nearby.’” Thomas got it—and lived near her workplace for the next thirty years. When she retired, in January 2011, she left a park with its core Olmsted & Vaux landscape restored, a deep reservoir of community goodwill, and a strong public–private partnership to help fund new projects. In 1980, none of those things existed.

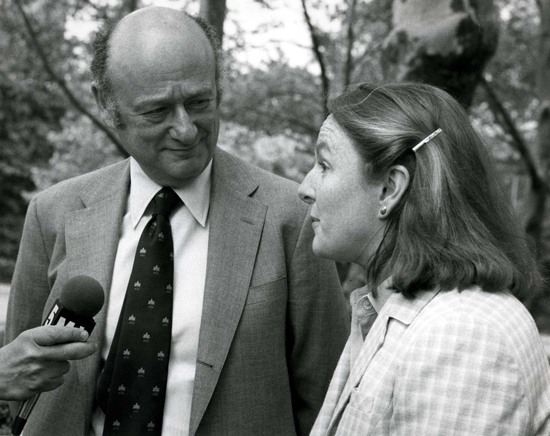

“Prospect Park was beautiful then, but scary,” Thomas recalls. Following a nationwide recession in the 1970s, most big cities lacked the funds to keep up park maintenance. Drug dealers and muggers overran the parks. In 1980 the doldrums began to lift. In New York City, Elizabeth Barlow Rogers led the formation of the Central Park Conservancy, which rapidly became a national model for public–private partnerships to fund urban park restoration. New York City Parks and Recreation Commissioner Gordon Davis reorganized the New York City Parks Department, and Mayor Ed Koch increased its budget for the first time in years.

Davis became a mentor and friend for Thomas, whose background did not include park experience. She had, however, worked for New York City in housing and urban renewal in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and she was passionate about the need to strengthen communities. Her knowledge of the park’s history came primarily from a course she had taken from the late urban historian and Olmsted scholar Albert Fein, who emphasized the social and political significance of Olmsted & Vaux’s city parks. “I’ve always viewed my job largely from that direction—what parks have done for community and democracy,” she says. That orientation made her ideal for this newly created position, one of several far-reaching innovations introduced by Davis. Up to that point, parks had been managed hierarchically, with park superintendents near the bottom, resulting in a limited scope of authority within the parks. “The idea of park administrators was to get someone to approach park restoration, operations, and maintenance holistically, and to engage the citizenry in the work,” explains current New York City Parks and Recreation Commissioner Adrian Benepe, who at the time was a ranger in Central Park. Once she started, Thomas promptly demonstrated her savvy. “She astutely mapped out which neighborhoods the ball-field applications and the events requests were coming from, and she approached city councilors and legislators all over the borough and told them, ‘Your constituents are using this park, and you should be funding it,’” Benepe recalls.

Thomas also saw that she needed to reach out to the press. It irked her that newspapers would sometimes report that a crime had occurred “near Prospect Park,” when it had happened a mile and a half away. “In New York City, that’s a long distance!” Thomas exclaims. “So, I’d call the reporters, invite them to visit the park, and show them how we were improving it.” Eventually, the papers reined in their inaccuracies, and Thomas gave them plenty of positive stories. In her first year she organized a family Halloween event and a New Year’s Eve fireworks celebration; both were instant hits that have grown into annual events attended by tens of thousands. “Great parks like this should have traditions that make people love them from cradle to grave,” she says. “That’s what makes communities and cities strong.” She also introduced education programs and formed a youth council that enlisted neighborhood teenagers to work in the park as peer leaders—a program so successful that it inspired a partnership with the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to launch, in 2003, the Brooklyn Academy of Science and the Environment, a public high school that integrates the missions and resources of both institutions.

In spite of these gains, by 1984 Thomas realized that she needed more funding to restore the park’s landscape, which was then 118 years old. The principal features of the Olmsted & Vaux design included the Long Meadow, the heavily wooded Ravine area, and the sixty-acre lake. Rolling meadows, carriage drives, woodland waterfalls, and a forest of maple, magnolia, and cherry enhanced the rural character, as did rustic structures and sandstone bridges. “In many ways it is the perfect city park,” says Benepe. “Here Olmsted & Vaux were not constrained by a narrow rectangle, as with Central Park, where high-rise buildings visible on all sides never allow you to leave the city behind. Prospect Park is an irregular diamond surrounded by low-rise buildings, which are not visible from deep inside the park. The illusion of the pastoral Picturesque landscape superimposed on the city is perfectly rendered here. The Long Meadow really does seem to go on forever. The Ravine seems like a forest of hundreds of acres, and the lake winds around to appear like an endless inland sea. This was all largely in tatters when Tupper started.”

Thomas had walked the grounds with Olmsted scholars, who pointed out how Olmsted and Vaux had intended these features to function aesthetically and physically. “To restore them, I needed to raise private funds, which meant starting a group like the Central Park Conservancy, so people could donate to an entity other than the city,” she recalls. After three years of planning, private citizens launched the Prospect Park Alliance, with Thomas as president, in 1987. “I had a good example in Betsy Barlow Rogers. Because of her groundwork, I didn’t have to establish why it was good or necessary to donate money to improve a public park. Every park in the country has benefited from that.”

In the mid-1990s, the Alliance launched a twenty-five-year restoration plan for the park’s 250 acres of natural areas, slightly less than half of its total acreage. The first phase restored the landscape in the forest core, including falls, pools, and surrounding woodlands. Next, workers continued stabilizing the Ravine. In 2000, the Ravine restoration was finished, and work began on a section of the waterway adjacent to it. “Restoring the Ravine was the most exciting project,” Thomas recalls. Whole sections of this dramatic feature had eroded. The park sits on a terminal moraine, which is far less stable than the outcrop of bedrock Olmsted thought it was. The park’s in-house design team, led by Christian Zimmerman, FASLA, reconstructed the Ravine from the bones out, documenting every step. Working in the park, Thomas realized how carefully it is designed, while appearing entirely natural. “It affects all of your senses,” she says. “They wanted to create a place that used nature to restore your soul. If you just go with that and don’t get too stuck on the path being two inches wider over here than over there, you don’t even have to say ‘historic preservation’—the design just works.”

Benepe comments, “Under her leadership, the essence of the park has been restored.” As her last project, Thomas worked with him on the Lakeside Center around the skating rink, which will restore twenty-six acres of parkland, replace the winter ice rink with a four-season facility, add five acres to the lake, three acres of green space, and a new green building, and restore the original Olmsted & Vaux design for the Lake and its shoreline. Thomas is excited not about the aesthetic effects per se, but about how they will benefit the people of Brooklyn. “Tupper has established the idea that citizens can play an active role in the lives of parks—not just large, well-heeled organizations, but individuals and groups like birders, responsible dog owners, and the teen council,” Benepe says. “She has made them all feel like this is their park.”

—Jane Roy Brown, former LALH Director of Educational Outreach.