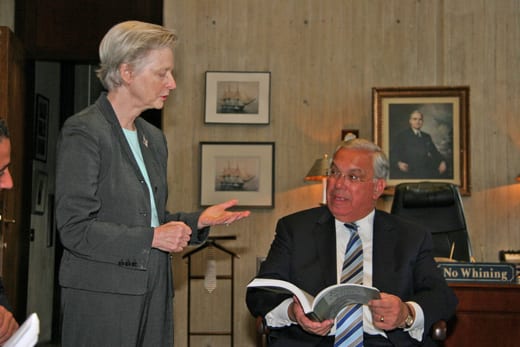

Caroline Loughlin, Cambridge, Massachusetts (2012)

“I didn’t know much about Olmsted except how to spell it. I don’t think I even knew that there was more than one of them,” Caroline Loughlin recalls, thinking back to the moment in 1989 when she was invited to join the board of directors at the National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP). She lived in St. Louis then, and had just coauthored a history of that city’s Forest Park. “But I knew about running a nonprofit organization, so I said ‘yes.’”

Faye Harwell, FASLA, Loughlin’s longtime volunteer associate at NAOP, recognizes that as a typical response. “The word ‘no’ is not in her vocabulary,” says Harwell, director of Rhodeside & Harwell, a landscape architecture and planning firm in Alexandria, Virginia, and Newark, New Jersey. That explains why, twenty-three years later, Loughlin has earned enough Olmsted “cred” to find herself among the country’s most active stewards of the firm’s landscape legacy. In addition to clocking hundreds of volunteer hours with NAOP—as cochair (twice), treasurer, and member of numerous committees—Loughlin has lent her rare combination of editing, archiving, and computer skills to tangible products.

These skills, she explains, are linked by her aptitude for logic, which she honed as an undergraduate at Cornell University, where she majored in math and excelled on the debating team. Immediately after graduating, Loughlin got a job at IBM as one of the company’s first female computer programmers. “At the time, IBM was one of few companies hiring women to do anything interesting,” she recalls. “It was wonderful—I loved it.” After marrying and moving to Florida and then St. Louis, Loughlin missed working with computers, so when desktop models became available in the late 1970s, she advised nonprofit organizations about how to make best use of them. “All that most people knew about computers then was the evil ‘Hal’ in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey,” she laughs.

It was only natural, then, that Loughlin connected with Olmsted scholars Charles Beveridge and Arleyn Levee, along with National Park Service staff members, to develop the Olmsted Research Guide Online (ORGO). “Part of what I brought was a certain ignorance, which allowed me to ask questions,” Loughlin says good-humoredly. “Anything you think you know about the Olmsted firm is more complicated than you know, and there’s more of it than you know.” What she knew well, however, was systems analysis and how to build databases, which proved invaluable, according to Lauren Meier, ASLA, who had helped launch the project. In 2005 NAOP recognized Loughlin’s invaluable volunteer contributions, especially to ORGO, with the establishment of the Caroline Loughlin Volunteer Service Award. With Meier and Lucy Lawliss, ASLA, Loughlin coedited The Master List of Design Projects of the Olmsted Firm, 1857–1979, another massive volunteer project that published in print some of the data that ORGO makes available online, combined with new explanatory essays.

Loughlin also has been an important member of the NAOP committee overseeing publication of the multivolume Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted series. “Most valuable for us at the Olmsted Papers has been Caroline’s strong leadership in making the Papers a major program of NAOP, following the project’s change of sponsorship after my retirement from American University in 2005,” says series editor Charles E. Beveridge, who also appreciates Loughlin’s success in securing private funding for the project at a time when federal funds are scarce. “But the most distinctive contribution,” he says, “is her direct involvement in the editorial work: she copyedited portions of the recently completed Volume 8, which covers the first years of the Olmsted office in Boston.” Her desire to assist came as a result of her actually reading the edited volumes, which gave her an appreciation of the value of the richness of Olmsted’s thought and writings. She is one of the very few people who have read all of the eight volumes we have published.” The editor of Volume 8, Ethan Carr, FASLA, an associate professor in the department of landscape architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and vice president of LALH, also appreciates her eye for detail. “She is an excellent copy editor and proofreader, as well as a scholar,” he notes.

Having moved to Massachusetts from St. Louis in 1999, Loughlin was geographically close by when Fairsted superintendent Myra Harrison and site manager Lee Farrow Cook invited her to be part of the group working to found Friends of Fairsted, in 2006. The nonprofit group is in a public-private partnership with the National Park Service for Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. “I have a good handle on what I can do and can’t do well,” says Loughlin, explaining why she willingly volunteered her administrative experience to the new organization. “So they took me in.”

Amid these ongoing commitments to the Olmsted projects, Loughlin also finds time to serve as a trustee of Mount Auburn Cemetery and was recently elected secretary. She also spends a full work day each week in the cemetery archives. When Loughlin first presented herself as a prospective volunteer, saying she enjoyed research, the cemetery’s curator of historical collections asked if she would be willing to start by copying and indexing the cemetery’s annual reports and trustee minutes. “I said, ‘Sure,’ without thinking about the fact that the cemetery was established in 1831! The only way I managed to get through it was to tell myself that these have sat here for a hundred years, so another week or even a month won’t hurt anything.” She eventually tackled several other long-term Mount Auburn projects, including the lot correspondence, which yielded the satisfaction of connecting back to Olmsted—albeit on a disconcerting note. “I found a letter from a cemetery official to Frederick Law Olmsted’s sons, delicately reminding them that their father’s cremated remains were still sitting there. ‘Please,’ he asked, ‘can you tell us what you want us to do with them?’”

—Jane Roy Brown, former LALH Director of Educational Outreach.