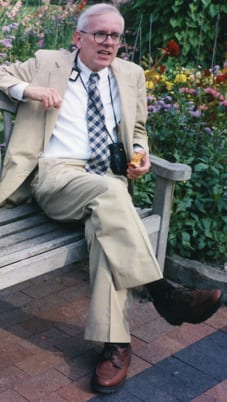

John Franklin Miller, Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan (2008)

John Franklin Miller first experienced the complexity of preserving historic landscapes while serving at Hampton National Historic Site, a Georgian mansion and landscape in Baltimore. “There were landscapes representing three periods in the property’s history, from eighteenth-century formal gardens to Victorian parterres to an English lawn,” recalls Miller, who was trained in architectural history.

But the authentic layers were compromised by twentieth-century additions that emphasized the estate’s first owners, whose ironworks supported the Revolutionary War. “It was very confusing,” Miller recalls. “It’s important to keep genuine changes visible, so that they read clearly to the public.”

Achieving that clarity, however, entails countless thoughtful decisions that may need to accommodate institutional politics, not to mention parking and accessibility requirements. “You have to make a lot of judgment calls,” he notes.

Miller, who is an LALH director and past president, brought these lessons to Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens, in Akron, Ohio, where he was chief executive officer from 1980 to 1995. “I was fortunate that four of the Seiberling children were living when I arrived. They had already built up a momentum to return to [Warren H.] Manning’s original landscape design of 1915.”

An exception is the 1929 English Garden created by the landscape architect Ellen Shipman, who was hired at Manning’s suggestion (he considered her “one of the best if not the best Flower Garden Maker in America”) to redesign the feature for Gertrude Seiberling. Rehabilitating the walled garden according to its Shipman plan was one of many projects Miller accomplished during his tenure at Stan Hywet. “Trees had shaded out Shipman’s sun-loving plants, and volunteers were maintaining it as a pretty shade garden,” he says. “But it wasn’t supposed to be a shade garden.”

Miller carried this advocacy to the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House in Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan, where he presided from 1995 until his retirement in 2007. He completed substantial architectural restoration and worked with landscape architect and Jens Jensen scholar Robert Grese to interpret the Jensen-designed landscape there. “I definitely raised awareness of Jensen’s importance and how crucial it was for us to understand what he was doing there,” Miller says. In 2003 the Garden Club of America recognized his work with an award for significant accomplishment in historic preservation.

“It wasn’t until Robin Karson started research for A Genius for Place that we fully understood Edsel Ford’s influence,” says Miller. “He was also very interested in landscape design, and Karson established that the combination of Ford’s and Jensen’s contributions made this property even more significant.”

He says such scholarship is “enormously valuable to any steward of a historic property.” Without grounding documentation, “preservation becomes the justification for doing almost anything. My philosophy hasn’t been to preserve whatever exists, but to identify the period of greatest historic significance, return the property to that period, and preserve that.”

—Jane Roy Brown, former LALH Director of Educational Outreach.