Landscape Preservation on a Forest Scale / Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, Woodstock, Vermont (2009)

Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, Woodstock, Vermont

“What does historic landscape preservation mean when applied to a working forest of 555 acres?” asks Rolf Diamant, superintendent of the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, in Woodstock,Vermont. Planted in 1874, the forest in question, which covers less than half of this former country estate on the eastern slope of Mount Tom, is one of the nation’s oldest surviving working forests, designed to showcase the period’s scientific forestry techniques.

The forest is rooted in more than utility: it embodies early conservation philosophy and ideas derived from the Picturesque style about how to use forests as scenery. The conservation ideas flow from George Perkins Marsh (1801–1882), who grew up on part of this property after the mountain had been clear-cut for sheep farming, leaving barren, gullied slopes and silt-choked streams. Marsh, at various times a lawyer, Congressman, and diplomat, witnessed even greater devastation caused by poor farming practices and deforestation in Europe and the Middle East, moving him to write the seminal work of the American conservation movement, Man and Nature (1864). Among those swayed by Marsh’s book was Frederick Billings (1823–1890), a prosperous businessman who, like Marsh, grew up in Woodstock.

Billings bought the Marsh property in 1869 and hired Boston-based landscape gardener Robert Morris Copeland (1830–1874) to plan the grounds. A decade earlier, Copeland had published Country Life: A Handbook of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Landscape Gardening. As William H. Tishler notes in his introduction to the 2009 LALH reprint edition of Copeland’s magnum opus, “In many ways . . . Country Life was intended as a book of rescue.” In it, Copeland urged farmers to embrace scientific methods developed to prevent the destruction Marsh would later document. Country Life also exhorted farmers to strive for beauty as well as utility.

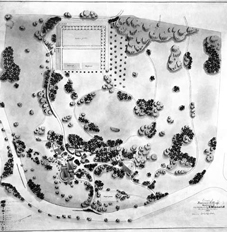

For Billings, Copeland created a plan that featured elements in the “Natural or English style” that Copeland’s book advocated: winding drives, clumps of trees, a summerhouse, greenhouses, flower gardens, and a kitchen garden. From the 1870s through the late 1880s, Billings reforested the mountain above the mansion, choosing species for both scenery and timber value, including Norway spruce, European larch, Austrian pine, European mountain ash, and white ash.

One of the property’s most striking features is a system of carriage roads, designed in the Picturesque style, interlacing the forest. “It seems that Copeland’s design approach was influential in Billings’s planning of the carriage-road system,” says Diamant, a landscape architect. “The mountain was deeply gullied by erosion, and Billings used scenic bridges and causeways to stitch it back together. It was both a pleasure drive and a working road.”

For one hundred and forty years, as the property passed down through Billings’s descendents, each generation continued the tradition of progressive forestry— planting, harvesting, and managing the forest using the best scientific principles available in their time. The last private owners, philanthropists Laurance S. and Mary French Rockefeller (Billings’s granddaughter), donated the estate to the National Park Service on the condition that the woodland would remain a working forest. “The issues raised in the formal gardens are ones we’ve had some experience with,” says Diamant, referring to the estate’s gardens, which were designed, at various times, by Charles Platt, Martha Brookes Hutcheson, and Ellen Shipman. “But managing a nineteenth-century working forest is preservation on a different order of magnitude.”

To arrive at a forest management plan balancing historic preservation, ecology, and visitor needs, Diamant and Christina Marts, the park’s resources management chief and also a landscape architect, focused on a few key issues: What were the dominant ecological forces? What species were there? How old were the trees? What plantation strategy emerged from these patterns? What are the historic features? How could the early forestry practices be made legible to visitors within the overall narrative of this place?

In broad strokes, the plan described a diverse, maturing forest with some open meadows, the opposite of the landscape that existed in 1874. “Ecologically, the conifers are creating conditions—increased soil nutrients, shade, and retained moisture—that now favor deciduous trees,” Diamant notes. Allowing for this ecological change (deciduous trees overtaking conifers), the plan recommends a gradual transition to more hardwoods while still preserving the landscape’s basic patterns. Specific character-defining features, such as the early stands of conifers found along the carriage roads and in other hallmark views, will be preserved. The plan recommends applying the best current forestry practices throughout the forest to demonstrate contemporary stewardship and retain historic character. In weighing these questions, Diamant has cast backward and forward in time, an exercise that highlights the fleeting nature of human effort: “Whatever we do now in this forest takes place in a different world from the one in which it was planted, as will be the case a hundred years from now.” (Related LALH books: Country Life: A Handbook of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Landscape Gardening; A World of Her Own Making: Katharine Smith Reynolds and the Landscape of Reynolda; A Genius for Place: American Landscapes of the Country Place Era; The Muses of Gwinn; The Spirit of the Garden; and The Gardens of Ellen Biddle Shipman.)

—Jane Roy Brown