Hefferlin and Becket gardens

Palm Springs, California

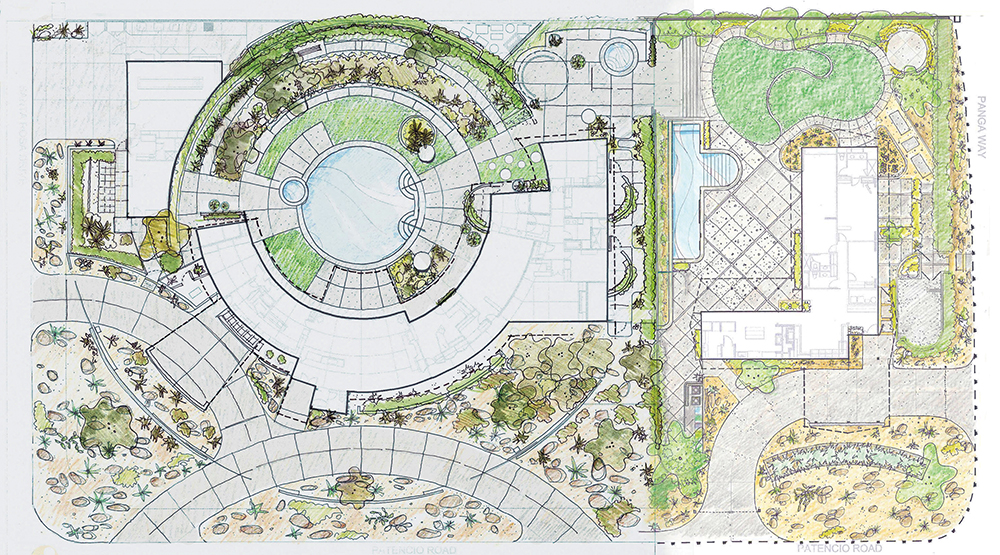

In 2007, the landscape architect Robert Royston (1918–2008) began work on what was to be his final design project, a residential landscape for Brent Harris and Lisa Meulbroek in Palm Springs, California. The garden is located on a one-acre site that slopes gently from south to north, with two architecturally significant modern homes on the property. The house on the northern end, designed by Welton Becket & Associates, was built in 1957. The larger home (known as the Hefferlin house in recognition of the couple who commissioned and built it in 1961), located on the southern end, was designed by the prominent San Diego architect Richard George Wheeler (1917–1990), with later additions by the architect Albert Frey (1903–1998). Both houses were completely renovated by the Harrises, who restored them to their original configurations, thereby opening the interiors to the gardens.

Over the course of his long and influential career, Royston was involved with thousands of projects ranging in size and complexity from regional land-use master plans encompassing hundreds of square miles to planter boxes that would sit comfortably on a small patio. The Harris garden is remarkable among them because it is both forward-thinking and retrospective. During the design development phase of the project, roughly January 2007 through the summer of 2008, when declining health prohibited him from travel, Royston and I met weekly to review progress of the design. In his distinctive approach to the Harris project, Royston applied a modernist design vocabulary and Cubist spatial concepts to the suburban California garden.

Royston began his professional life while still a student in the landscape architecture program at the University of California, Berkeley. On the recommendation of one of his professors, he joined the office of the renowned landscape architect Thomas Church in 1937. Working on Saturdays and during summer breaks, Royston became familiar with the tools of his profession during a period of unprecedented change. By the late 1940s, postwar prosperity, advances in technology, and a surge in population had led to the development of new building types demanding new landscapes, as well as a modern design methodology appropriate to the times. Returning from military service in World War II, Royston left the Church office to join the next generation of modernist practitioners.

In his partnership with Garrett Eckbo and Edward Williams, Royston produced some of his most outstanding residential work—plans that illustrate his skill in manipulating space as well as his attention to subtle detail. In the first years of the partnership, roughly 80 percent of the new firm’s commissions were gardens—“fun projects,” in Royston’s words, that allowed him to develop relationships with clients who were willing to experiment with new ideas. Inspired by modern art, Royston put the dramatic arcs, asymmetrical grids, and amoeba-like forms characteristic of the modernist style to practical use as he created engaging, functional spaces for outdoor living. His gardens were carefully choreographed to fit his clients’ lifestyles, but he also strove for a sense of timelessness in his designs.

In 1958, Royston, Eckbo & Williams parted amicably, and Royston launched his own firm, building on the collaborative, interdisciplinary model developed with his first partners. The successor firm, Royston, Hanamoto & Mayes, quickly acquired important residential and civic commissions. The firm’s expansion into public work was particularly meaningful for Royston, who saw his park designs (he called them “public gardens”) as the natural evolution of his residential work and important contributions to the larger framework of the urban and suburban environment. The firm he established continues today as RHAA Landscape Architects.

Royston initiated work on the Harris garden with a site visit. Standing at the edge of the property on a sunny May afternoon, he conceptualized several large zones that would define the garden. Observing that it was common in the neighborhood to enclose gardens with block walls, metal picket fences, and tall hedges, Royston suggested a more gracious arrangement of walls and hedges for the Harris site, since “we don’t want it to look like a fortress.” This boundary established an area of transition from the public street to the privacy of the home. To accomplish Royston’s vision for “authentic desert,” more than two hundred tons of stone closely matching local geology would eventually be placed at the perimeter of the property and populated with regionally native plants.

The largest of the private spaces in the oasis zone of the Hefferlin house is circular, centered on a large swimming pool defined by the radial floor plan of the circular house. “Those angles,” he observed, “control the view out from each of these rooms. They direct the eye to the center.” When discussing his plan for this area of the Harris garden, Royston pointed to a painting by Wassily Kandinsky, Several Circles, as his inspiration for the design. He added additional circular forms: a fountain with a waterfall to enliven the surface of the pool, curbed planting areas, low garden tables, and planters in an asymmetrical arrangement. He also proposed large circular floats for the pool, which he called “lily pads,” to add movement to the composition, although these were not included in the finished garden.

A concrete block wall to screen the back of the garage had been built as part of the building remodel. For further spatial definition of the pool garden, Royston added a curved bench that completed the circular space around the pool. A curving walkway leads to a raised lawn and bench, creating a quiet and more intimately scaled place to sit and look down into the garden. Three tall Mexican fan palms were relocated from another part of the property to provide a soaring vertical counterpoint to the flat planes of turf, concrete paving, and water.

The terrace adjacent to the Hefferlin house sunroom acts as a transition between the two properties. Royston took advantage of the Albert Frey–designed addition to create a strong and direct connection to the garden and furnished it with a garden pavilion (relocated from the pool garden), an in-ground spa, and circular garden tables and planters set close to the ground for dramatic effect. From there, visitors can move south into the Hefferlin pool garden, north to the Becket garden, or east to private patios located adjacent to bedrooms in the Frey addition. Anticipating the need to separate the gardens at times, Royston designed a rolling gate that matches the height of the adjacent block wall

Royston believed strongly that every garden should in some way be “a gift to the street,” and the plantings along the street frontage of both houses are such gifts. He directed that where possible, existing mature plants should be retained and pruned to reveal their sculptural qualities. He specified that foliage should be gray or muted green and that flower color be limited to yellow and white—colors, in his view, appropriate to his idea of “authentic desert.” For the back garden at the Becket house, Royston arranged vertical picket screens to shield the outdoor shower and a utility area from view. He also employed a semicircular screen to define and enclose a seating area. Beyond their utilitarian functions, these compositions generate a series of complex spaces on the edges of the back garden.

Royston spent considerable time working out the size and shape of the lawn panels and insisted that the concrete score pattern for the large terrace be rotated at a 45-degree angle to the house. In pursuit of a strong ground plane pattern, he also suggested that the paving be two-toned. This was in the end changed to a subtler color variation achieved by sandblasting pavement surfaces.

In the adjoining gardens, Royston created a half dozen intimate areas. Three of these small garden retreats are found at the Becket house—the small screen-enclosed seating area on the northwest corner of the back garden and the private patios located on the north side of the home. In the Hefferlin house garden, small walled patios are sited outside the sliding doors of the bedrooms on the north side of the house. The garden pavilion on the sunroom terrace provides a retreat comfortable for a small group, and a bench set at the back of the garden is suitable for a single person.

Using tools developed over a lifetime of practice, Robert Royston conceived a remarkable series of modern spaces for the Harris garden. During the weekly design meetings, he sometimes commented on the declining state of his health. “I’ve only got two things going on right now,” he joked, “appointments with doctors and this garden.” If he felt that this might be his last project, Royston, ever the optimist, never mentioned it. But on some level he seemed to understand where this design fit in the grand scheme of his work. Revealing a direct and purposeful reaching back to solutions conceived decades earlier, the Harris garden also reflects a deft adaptation of these ideas to the personalities of the clients and the specifics of the site, and, in this sense, remains timeless.

Read more about Robert Royston’s life and work in Reuben M. Rainey and JC Miller’s Robert Royston.