Cape Cod National Seashore

Massachusetts

Few visitors to Cape Cod National Seashore realize that the renowned park is the product of an unprecedented effort to save a cultural landscape. Faced with increasing development throughout the region, a remarkable generation of Cape Codders recognized that the very essence of the Cape was at stake and pushed their congressional delegation, the National Park Service, and their neighbors to develop a new approach to landscape conservation. The “Cape Cod model,” the compromise that ultimately resulted, considered the six towns of the Upper Cape and the lifestyles they represented as unique resources defining the region and therefore worthy of stewardship.

To a greater degree than possibly any other tourist destination in the country, the appeal of Cape Cod combines people and place, cultural history, and natural beauty. Henry David Thoreau, arguably the most important Cape Cod tourist, significantly shaped early impressions of the region. Although replete with descriptions of shorelines, dunes, wetlands, and harbors, as well as specific accounts of plants and animals, Thoreau’s narrative is most notable for descriptions of long-standing residents of the Cape—sea captains, Wellfleet oystermen, and “wreckers” who scavenged shipwrecks. In his observations of the 1850s, later published as a popular travel account and still reprinted today, Thoreau recorded both the imminent passing of one Cape Cod and a rising awareness of another. Cape Cod remained relatively isolated through much of the nineteenth century, unlike other coastal resorts in New England. The twentieth century brought rapid development, however, turning abandoned farms and depressed town centers into destinations for summer vacationers. Improved roads and affordable automobiles opened the region to tourism, and by the 1930s, the Cape had assumed its place in the popular imagination as an idyllic and still unspoiled landscape of beaches, scenery, and unique cultural heritage.

By the 1950s, though, the erosion of the charm of Cape Cod was evident to many. The scale and type of construction changed abruptly during the postwar era. Midcentury modernism became a dominant architectural idiom, and new, larger motels, restaurants, and other businesses lined busy highways. Residents and summer visitors alike became increasingly aware of the environmental damage to fragile dune, wetland, shoreline, and forest ecosystems. To those who were settled in the remote wilds of the Cape, the impending development was threatening, but others protested against zoning, restrictions to off-road vehicles on the beaches, and protection of endangered habitats. The visionary plan to create a national seashore succeeded only through intense campaigning, as the National Park Service and like-minded Cape Codders worked to convince entire communities of the long-term value of a park that could accommodate millions of tourists. Years of contentious negotiations resulted in the innovative compromise between private and public interests now known as the “Cape Cod model.”

The Cape Cod model allowed property owners to live within park boundaries, while Congress appropriated funds to acquire the remaining private land for a new national park. The resulting mosaic was a physical one, with private inholdings appearing throughout the public reservation, but it was a social fabric as well, with the threads of private, town, and federal interests interwoven throughout. For the idea to work, the six towns of the Outer Cape within park boundaries needed to pass zoning laws. Although the use of eminent domain was authorized when necessary, existing “improved properties” were allowed, as long as the towns created zoning districts within the seashore’s boundaries to restrict any future development.

President John F. Kennedy signed the legislation establishing Cape Cod National Seashore in 1961, initiating a new era in national landscape conservation. The park was then shaped by two influential planning efforts: the 1963 master plan, which had determined the basic development of buildings, roads, parking lots and programs; and the master plan published in 1970, which initiated an era of protective management of both natural and cultural resources. Both plans set precedents and made the park a showcase of contemporary priorities in the national park system. The challenging process of land acquisitions, which took until the 1980s to fully resolve, dramatically altered the trends and patterns of development of the Outer Cape landscape at a critical point in its history. The National Park Service would go on to apply the lessons learned at Cape Cod National Seashore throughout the national park system.

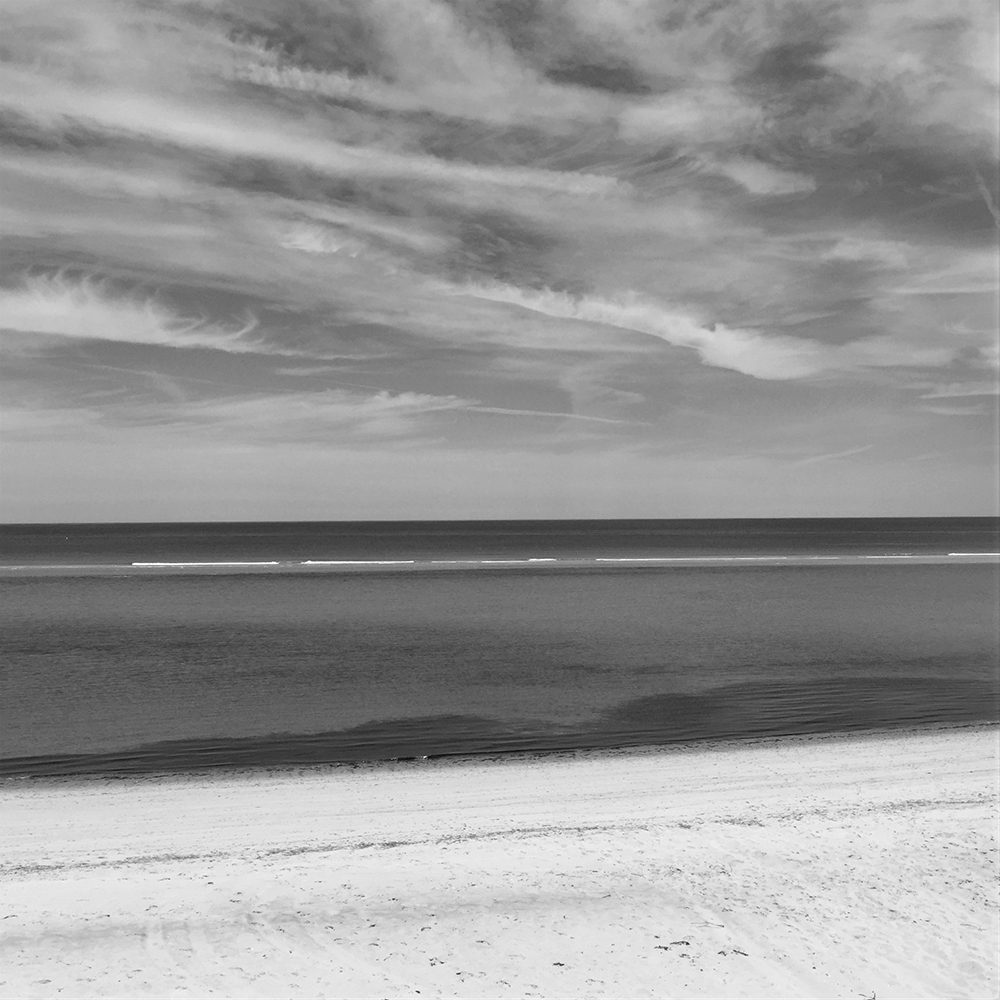

Photographs by Carol Betsch

Learn more about Cape Cod in The Greatest Beach: A History of Cape Cod National Seashore.