Beginning in the late nineteenth century, new fortunes in the United States made it possible for many city-dwellers to commission country estates. Wealthy industrialists could work in town, and, by train or automobile, escape deteriorating urban centers to enjoy healthy air and breathtaking scenery, even at the end of each day. A widespread belief in the cultural and salutary benefits of rural life, plus the availability of money, prime land, and growing legions of professionally trained landscape architects, set the stage for ambitious residential landscape designs across the country. From 1895 to the waning years of the Great Depression, thousands of American estates were created from Mount Desert, Maine, to Santa Barbara, California. Together their designs comprise an important, virtually unexamined art movement. Seven such places are the subject of this photographic exhibition.

American landscape design before the Country Place Era was shaped largely by the ideas of Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852) and Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903), both of whom designed home grounds in a romantic, picturesque style, while also responding to the “spirit of the place”—the genius loci. By the end of the century, wealthy Americans had begun to develop more Eurocentric tastes, particularly after the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Inspired by the Beaux-Arts buildings and plan of the fabled White City, by grand tours of Europe, and by new magazines and books such as Charles A. Platt’s Italian Gardens (1894), many patrons requested features seen in England, France, and Italy for their American country homes and gardens.

In the years following Olmsted’s death, strong polarities divided the field. The stylistic battle between formality and naturalism—viewed as more distinctively American—took on a regional cast. Many midwestern landscape architects looked to indigenous plants and naturally occurring landforms for design inspiration; those practicing in the East tended to be more interested in Europe. The period’s most artistically successful landscape designs integrated the two poles of inspiration, deriving vitality from each.

During the 1910s, a host of other influences came to shape increasingly eclectic landscape designs. Gardens became more personal as landscape architects were asked to design private landscapes to not only satisfy their clients’ day-to-day needs but to express their horticultural passions, remind them of their travels, or provide settings for their collections of sculpture. Many projects—including those in this survey—were the result of long collaborations between landscape architects and clients, whose sophisticated ideas often challenged convention. Women, able to breach gender barriers in the profession through their long-standing association with domestic gardens, brought unique horticultural skills and cultural perspectives to the art of residential landscape design. All these forces contributed to a heightening of the imaginative quality of landscape design.

In the 1920s and 1930s, an increased emphasis on abstract color, form, and space in gardens reflected the influence of French modernism and other developments in painting and sculpture. The era’s most artistically distinctive gardens continued to be guided by the force of the genius loci—expressed as a celebration of view and the ineffable spirit of place. The greatest American gardens of the period integrated this celebration with artistic expression.

As fortunes shrank during the Depression, the demand for American country estates diminished, and when the United States entered World War II in 1941, private construction ceased altogether. After the war, land use patterns changed dramatically and the unique set of cultural and intellectual circumstances that had given birth to the Country Place Era dissipated. Since that time, most of the era’s estates have disappeared, too. But the examples in this exhibition do survive and most are now accessible to the public. By illuminating their meaning, we hope to encourage thoughtful stewardship of them and of other significant American landscape designs.

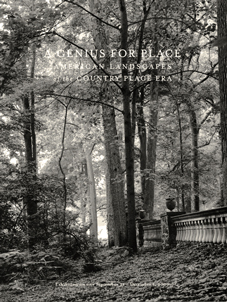

Exhibition Brochure