John Nolen’s Union Park Gardens: Where Neighborliness Abounds / Wilmington, Delaware (2014)

Wilmington, Delaware

“Visitors from other parts of the city often tell us that they never knew this neighborhood was here. I had the same reaction the first time I came to see Union Park Gardens—it’s a refreshing surprise,” says Brian McDerby, a state trooper who has lived for ten years in this residential enclave of Wilmington, Delaware.

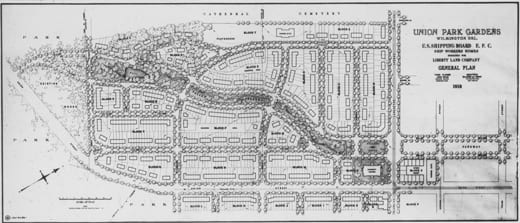

What makes Union Park Gardens a surprise, McDerby says, is its park-like setting, which remains intact nearly a century after the landscape architect and town planner John Nolen (1869–1937) designed it to provide emergency housing for World War I shipyard workers. In 1917, a government-funded developer bought a rolling, 58-acre tract in the southwestern corner of Wilmington. Here Nolen and architects of the Philadelphia firm Ballinger & Perrot designed a “garden suburb,” as Nolen called it in his book New Towns for Old (1927). Despite a density of more than 500 houses on 32 acres (about 16 houses per acre)—achieved by building mostly attached and semi-detached houses, grouping garages on a few streets, and eliminating driveways—Nolen and the architects managed to create a respite from the stress of urban life within the city limits. Curving tree-lined streets, a broad parkway, and a linear park contribute to its naturalistic character, as do the irregular shapes and sizes of housing blocks; yet a legible order rules.

“John Nolen was remarkable in his ability to create such a pleasant environment,” says Adele Meehan, who moved here from Philadelphia in 1996. “It’s like being in the suburbs, but we’re in the city. We can walk easily to restaurants, and buses now run into town along the two original trolley routes.” And, she says, because of the low-traffic streets and wide sidewalks, lots of people like to stroll within the neighborhood. As a result, neighbors tend to meet neighbors. “On nice days people are out walking their dogs, stopping to chat,” says Mark Bacher, who lives on Meehan’s block. “There is a sense of connection. On my street we all have keys to one another’s houses. We look after each other’s pets.” McDerby and his wife, Julia, are raising a young daughter on the same street. “On Halloween the people on our street start out on their own porches and wind up congregating in one of our driveways,” he says. “Because it feels so safe, sometimes parents from other parts of the city bring their kids here to trick-or-treat to give them that experience.”

Although these residents love the neighborhood, they also acknowledge that century-old worker housing doesn’t quite fit this age of living large: a typical semi-detached, two-story house contains six rooms (one bath, three bedrooms, kitchen, living room, and dining room), the largest of which is 11.5 feet by 12 feet. John Krill, a retired art curator, has lived in a house like this with his wife, Rosemary, since 1983. “A tall friend says our house is ‘bitsy,’” he says. Even though they raised their son here, Krill knows that few couples would be willing to do that today. The McDerbys, an exception, agree that it would be untenable for them without a finished basement with an extra bathroom added by a previous owner. Therein lies one of the main preservation threats to a planned community in which architectural proportion underpins the prevailing harmony. Over the years, homeowners have sought to stretch their living space by tacking on outsized decks and other additions. “Most additions to these houses look like warts, because people don’t keep the proportions and materials consistent with the existing design,” says Krill.

Since Union Park Gardens lacks official historical recognition, it has no protective preservation ordinances to watchdog such changes. Debra Martin, Wilmington’s Historic Preservation Planner, says the suburb “is certainly a candidate for the National Register of Historic Places, but in the past I have understood that residents were not of one mind about it.” A National Register listing requires extensive documentation, but it rewards the effort by qualifying residential property owners for state tax credits, and it raises awareness of a property’s historical value, which tends to discourage haphazard alterations. Changes to buildings don’t require federal oversight unless owners receive federal funding or permits to do the work. Union Park Gardens residents could also seek City Historic District zoning, which offers tax abatements but requires review of proposed changes by city officials. So far, the community has yet to pursue either option.

For years, Adele Meehan has served as de facto preservation champion for her community. “I want to educate younger residents about the neighborhood’s fascinating history, so that they respect the original design of the buildings and the neighborhood as a whole,” she explains. Since LALH published a new edition of Nolen’s New Towns for Old in 2005, she has used it to raise awareness of the community’s historical significance. Meehan has also hosted visiting scholars, including Charles D. Warren, who wrote the introduction to the LALH edition, and R. Bruce Stephenson, author of the forthcoming LALH book John Nolen, Landscape Architect and City Planner. Meehan also has presided over the community association and edited its newsletter. She sits through numerous city meetings, alert for potential threats—such as a recent attempt to reroute Interstate 95 through the community—so she can rally residents to act (successfully, in this case).

”People in the neighborhood are probably more aware of the history and significance of this community than at any other time, and Adele has been the force behind this,” says Bacher. “When the Nolen book came out, she did a lot of research and created a presentation made available to the community on numerous occasions. She worked for years to install a historical marker about Nolen at the entrance to the neighborhood.”

Meanwhile, crime may pose a more pressing threat to the community than unsightly decks. According to McDerby, abutting neighborhoods have succumbed to a wave of gang-related activity during the past few years. So far, Union Park Gardens residents have experienced only minor incidents, such as parked cars getting rifled, perhaps because of the high number of city firefighters and police who live in this affordable neighborhood. But if crime creeps closer to home, “it would force us to decide whether to move,” McDerby says. “The problem is, we’d want to take our whole street and all of our neighbors with us.”

—Jane Roy Brown