Going Native: Lockwood de Forest and the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

The dispute came down to the shape of a line.

In 1943 two prominent American landscape architects, Beatrix Farrand and Lockwood de Forest, argued over plans for the path visitors would take as they entered the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, where both served as design consultants. Farrand advocated a straight, direct line, an axial path that would highlight the newly built administrative complex and connect the architecture with the meadow and mountain beyond. De Forest disagreed. The path, like the trails that already wound through the garden’s varied terrain and linked its diverse ecosystems, should, he insisted, meander from the start, with the new building hovering at the periphery of a visitor’s attention, incidental, like an afterthought.

Lockwood de Forest wrote to Farrand from Los Angeles, where he was assigned to a wartime camouflage unit, to express his objections: “The formal setting of the new Library building is far too important for such an inconsequential bit of architecture. . . . I should like to see as much of the building covered by planting as possible. After all, the garden is a botanic garden for native plants and not an architectural exhibition.”

For Farrand, though, that building, designed by another prominent Santa Barbara designer, Lutah Maria Riggs, signaled the Botanic Garden’s coming of age. “The Garden has passed from its first experimental and somewhat haphazard stage,” she wrote to its benefactor, Mildred Bliss, “into an important unit which should be treated with dignity of design.”*

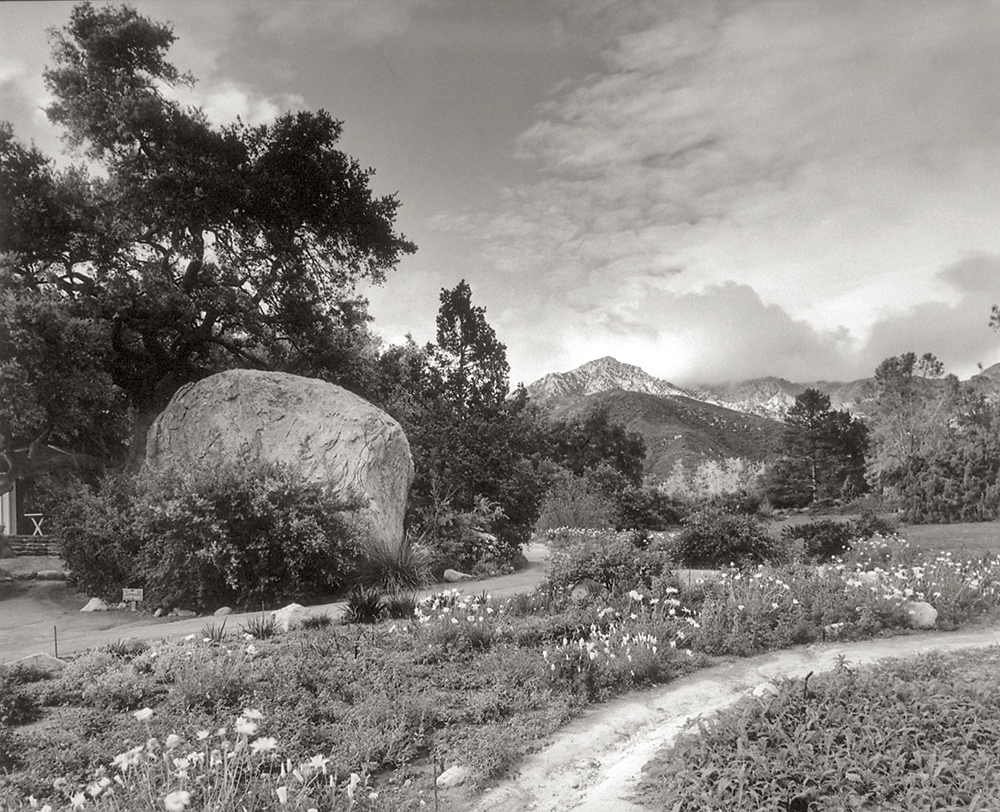

Lockwood de Forest, who was my grandfather, was known for his casual manner. He often worked, my father recalls, without plans, sketching his ideas on the spot. Whether Farrand intended her words as a pointed jab at her younger colleague or not, my impression is that for my grandfather the haphazard and experimental constituted not only the Botanic Garden’s beauty but its very purpose and essence. No mere romantic gesture, the shape of that entry path meant everything to him. As soon as visitors stepped onto the path and were gently led to a magnificent vista—a sprawling, blooming meadow anchored to a giant boulder, a natural feature of the terrain left undisturbed by human intervention, the lofty triangle of Cathedral Peak rising behind, distant, yet remarkably near—they would know that they had entered a place like no other. That meander away from the main buildings expressed what made the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden distinctive and hinted at the encounters with nature to expect there, curving away from the man-made artifice of architecture and into a wilder, natural world.

From its founding in 1926 as part of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, the Blaksley Botanic Garden, as it was first known, was envisioned as something new and unprecedented. Ervanna Bowen Bissel, the garden’s first designer and wife of the garden’s second director, Elmer Bissel, wrote in 1930: “Blaksley Botanic Garden is an exhibition garden; its aim is to grow attractive plants native to the Pacific Slope; its plan is to set these plants in communities, artistically arranged; its object is to show the beauty of native plants and their adaptability for use in private gardens; and its slogan is Back to the Soil—with native plants. Back to California’s soil—not with thirsty exotics—but with California’s drought-resistant plants which conserve the state’s water supply.”

The Botanic Garden’s mission was, from the first, educational and experimental—an inspiring showcase for native plants that could thrive in California’s arid climate and would inspire home gardeners, as well as local nurseries, in cultivating and planting their own gardens. That unprecedented mission demanded a bold new design as well. The native plants were not displayed as individual specimens but arranged in ecological communities in an expansive parklike setting. Tucked into the upper reaches of Mission Canyon, at the base of the Santa Ynez Mountains, the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden became, as its design and mission evolved over the next decades, a fluid ensemble of distinctly California environments, from flowering meadow to dense forest to sparse desert, all adapted to the particularities of the coastal climate and canyon terrain.

Traditionally botanic gardens have been cerebral experiences. Though not without their aesthetic delights, botanic gardens from Kew to Florence to Berkeley present an orderly sampling and sequence of plant specimens, grouped by either botanical or regional classifications, the outdoor equivalent of a museum or library. It’s not surprising that my grandfather, who had no truck with formal education, collaborated on designing an educational garden that was more experiential than intellectual. His stints at East Coast boarding schools, and then again at Williams College, were brief. The only place where he thrived was Thacher School, in Ojai, California, where he rode horses and camped in the back country of the Matilija wilderness. It was at Thacher that he fell in love with the California landscape, climate, and terrain. There, he received his true education. Transplant from a New York City upbringing though he was, he loved the California hills—gold in summer, green in winter, bright with poppies and lupine in spring. This felt to him like native soil, perhaps because it was there he finally flourished. An educational garden that was organized formally would be antithetical to the improvised, hands-on, kinetic way that he preferred to learn. If a garden was going to be a teaching tool, let it teach through immersion.

So, for the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, he designed a system of trails that, still today, draws visitors into an immersive, sensory, and in some places physically challenging experience. Today, the entry path flows seamlessly past the meadow and then offers choices, divergences, opportunities for exploration and discovery. One direction descends into desert dryness, another to dense forest, where the trunks of redwood trees seem to exhale coolness, even in full summer. Visitors climb, descend, cross a creek, scamper across rocks, face the looming triangle of Cathedral Peak, or climb again and are rewarded with the panorama of the Pacific stretching blue, dotted by a chain of Channel Islands. The environments and the plants that define them change, but the trails that my grandfather designed unify these spaces into a single experience, a single, expansive garden.

As many historians have noted, the tiff between Farrand and de Forest was short-lived, and resolved in my grandfather’s favor. One could chalk up the argument to a clash in style and manner: Farrand nearly a generation older, formal in taste and habits, an easterner; de Forest, a twentieth-century innovator and casual Californian, a “maverick,” in the words of the landscape historian Susan Chamberlin. In reality, they shared many aesthetic affinities. Both brought a painterly sense of color, line, and texture to composing garden spaces that impart an air of ordered spontaneity. The Botanic Garden’s centerpiece, the sumptuous, oval-shaped wildflower meadow, represents a true collaboration, a fusing of the two sensibilities.

Still, the argument over the entry path came down to a fundamental question: in a botanic garden devoted to the native, the natural, the wild, what is the human’s place and role? Farrand’s path, by framing and favoring architecture, asserted the human propensity for order in a landscape. Her design, she believed, reflected the Botanic Garden’s maturity and seriousness of purpose. Architecture’s formalism would tame and temper the garden’s wildness, and, in taming it, make it more accessible.

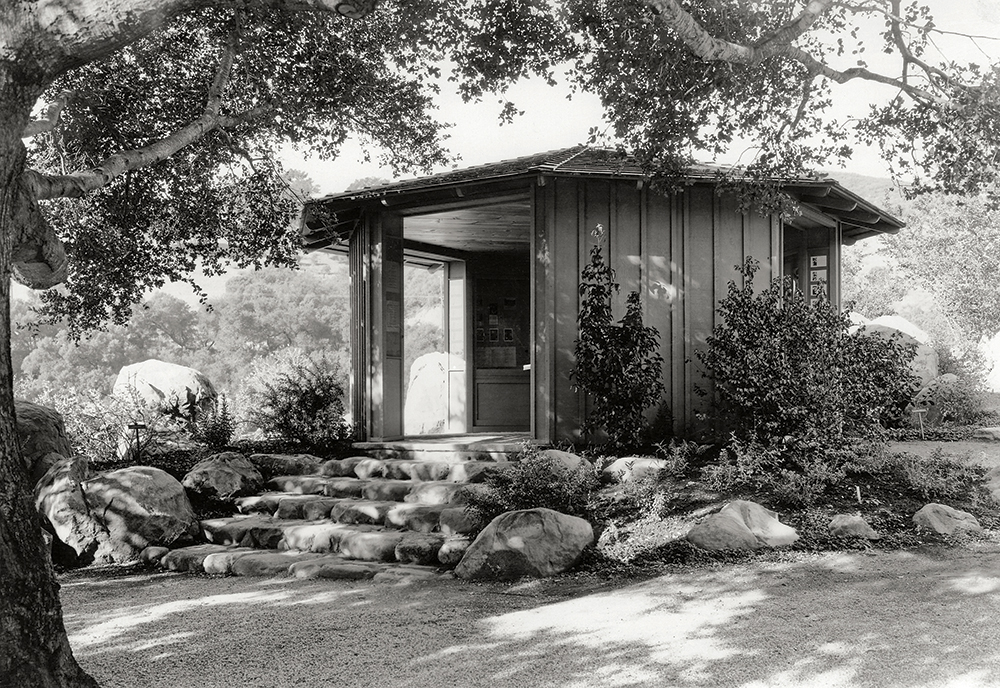

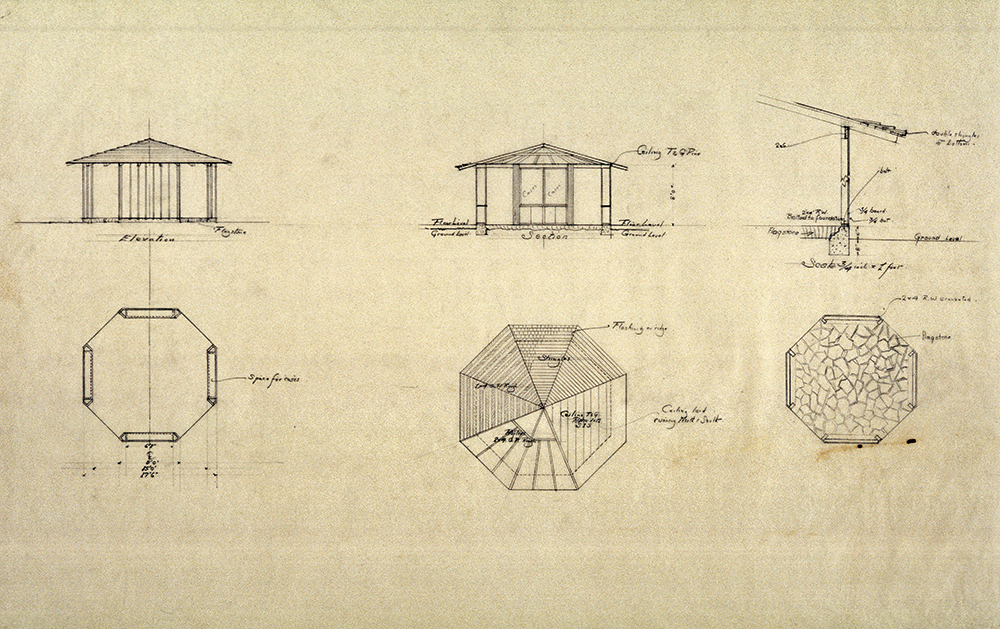

My grandfather’s approach (figuratively and literally) gives the human a humbler role. Rather than order, organize, catalog, or even acquire information (though the plants are well labeled) as one meanders through, the visitor simply absorbs. The Botanic Garden calls visitors to be walking witnesses to the wild proliferation all around them. Lockwood de Forest’s design and siting of several architectural elements in the garden reveal his perspective on this human intervention. The open, rustic information kiosk he designed near the entry in 1937, or the Campbell Bench, hewn from stone and curving against a massive boulder, which offers a shady place to sit at the end of a sun-soaked trail and take in the view, are two built features that emerge organically from the landscape, as if they have always been there, as natural and inevitable as the rocks and the trees. Like a well-placed trail sign, they appear just when a visitor might feel in need of direction, rest, or shade.

My grandfather was involved in shaping the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden for his entire career—from its founding and formation in 1926, when as a young practitioner he advised the director on native, drought-resistant plants, to his untimely death in 1949, when he was completing the rugged Pritchett Trail, with its dramatic overlook to the Channel Islands. The battle over the path seems to have struck a deep, personal chord. Before he wrote to Farrand, he “registered his disapproval” to the board: “I feel a little like the private who had discovered someone wanted to put an army camp on Mt. Tamalpais. He wrote if it was spoilt he didn’t see what he was fighting for.” For my grandfather, I believe, the argument was not about aesthetics, but ethos. This disagreement, minor though it may seem, was a fight for the garden’s very soul—and possibly his own as well.

In searching for my grandfather in the spaces he designed, I find that the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden may be the fullest expression of his identity still extant. Unlike many designers, he was less inclined to make his mark on a place as to cultivate, in this community of spaces, a place that would leave its mark on him.

As I was writing this piece, a friend who used to visit Santa Barbara every October with his family, told me how his young sons, untraditional learners like my grandfather, responded to the Botanic Garden: “However sophisticated and innovative these spaces are, it remains to me powerful that a child immediately recognizes the worth of these places, their possibilities. And the ease of moving within them is immediately accepted in the running feet and laughter of children.” The Santa Barbara Botanic Garden today, guided by Lockwood de Forest’s ethos, leaves a mark on anyone who embraces the possibilities of those beautiful spaces and travels those winding trails.

Ann de Forest writes fiction and nonfiction that often centers on the resonance of place. She is a contributing writer for Hidden City Philadelphia and editor of Extant, the magazine of the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia.

*All primary source quotations and much of the information in this essay are drawn from the comprehensive history written by Mary Carroll for the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden in 2003. Similarly, Susan Chamberlin’s “Lockwood de Forest ASLA and the Santa Barbara Landscape” in Eden, Journal of the California Garden & Landscape History Society, summer 2014, was an invaluable resource.