NPS DESIGN TRADITION IN THE 21ST CENTURY

This essay first appeared in the George Wright Forum, published by the George Wright Society.

Centennial celebrations, like most historical commemorations, express apprehension for the future as much as pride in the past. While retrospection on an important anniversary can forge renewed identity or purpose, the need for such definition seems most pressing when new realities call old certainties into question. The National Park Service (NPS) has important reasons to celebrate its centennial, in this sense. It comes at a time when social, technological, and environmental changes have already altered basic assumptions about national parks and their management.

This is not the first time the NPS has made such use of the anniversary of its 1916 Organic Act. In 1955, Director Conrad L. Wirth anticipated the agency’s fiftieth anniversary as the deadline for a ten-year expansion and modernization of the national park system, and of the NPS itself. Then as now, demographic and technological changes were shifting how, where, and when people visited parks, and the kinds experiences they had when they did. Wirth and his cadre of park planners and designers were prepared to rethink fundamental aspects of how park visits should be facilitated. He named the effort “Mission 66,” and the program is best known today for the many construction projects—visitor centers, park housing, utilities, road widenings—completed through increased annual appropriations during the decade leading up to 1966. Many of the developed areas of the national park system still rely on the automobile-oriented infrastructure of the Mission 66 era. But Mission 66 also provided for an increase in the size and professional training of NPS staff, and it permanently raised expectations for overall levels of annual funding per unit of the system. Initiatives in the identification and restoration of historic sites prefigured the preservation legislation of the 1960s. The planning and development of national recreation areas and national seashores stimulated further recreational planning on the federal scale. Critics have condemned Mission 66 for relying too heavily on park development to meet the challenges of post-World War II war levels of use. But as a ten-year long, billion-dollar fiftieth birthday party, it will be an hard act to follow.

Of course the “mission” in the twenty-first century is very different than that of the mid-twentieth. The baby boom may be over, but demographically we are a more diverse nation and that trend will intensify. While the construction of the Interstate Highway system made parks more accessible to the public than ever before, today new sources of information and experience available through the Internet make it possible to “visit” places without actually traveling at all. As the seemingly endless rise in visitor numbers slows or even reverses, fears that parks are being “loved to death” are accompanied by another apprehension: that parks are being ignored, and are becoming irrelevant to the younger generations who must become their stewards. And if it once seemed to be possible to protect a park’s integrity with physical redevelopment plans meant to minimize visitor impacts, new threats such as climate change, sprawling urbanization, and habitat loss make it clear that ecological threats are global in scale and are neither contained, nor entirely mitigated, within park boundaries. The twenty-first century already mandates a new “mission.”

To the degree that NPS officials have articulated goals for marking their agency’s centennial, it is fair to say they have not yet done so with the emphatic clarity that Wirth gave to Mission 66. Neither has Congress indicated it might initiate a new era of capital investment in the national park system. The NPS today is in a completely different position politically, legislatively, and administratively than it was in the middle of the last century. Federal environmental legislation and agency policies, for example, long ago determined that another Mission 66 could not, as well as should not, be attempted. Wirth’s NPS was still a park development agency, as it had been since its creation in 1916. It relied on landscape architects and engineers to design plans for “harmonious” park improvements that would enable growing numbers of visitors arriving in automobiles to “enjoy” scenic and historic places without “impairing” them. By legal definition, the purpose of the national parks was to preserve them unimpaired for the benefits they offered the visiting public.

[peekaboo_content name=”ECblog3″]

This definition has often been described as oxymoronic, or at least as a dual mandate. But Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., (who wrote the key portion of the 1916 act expressing this purpose) believed that the design and construction of public park facilities—roads, trails, campgrounds, and other public and maintenance areas—made it possible to achieve both enjoyment and preservation, at least if such development were done well. His father was the source of this belief. Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., in his 1865 recommendations for the management of Yosemite Valley, unequivocally prioritized the first goal of that new park: landscape preservation. The second and also vital mandate was to establish easier public access to the park, and to develop drives, paths, and minimal facilities within the park to allow visitors to experience it without damaging the fragile landscape. Olmsted asserted that appreciation of landscape beauty—whether in the middle of Manhattan or in the remote Sierra Nevada—was necessary to the physical and emotional well being of individuals, and therefore to the future public health of the Republic. The creation of public parks, in this light and along these lines, was nothing less than a required duty of government.

Olmsted’s 1865 Yosemite Report was ignored in the coming decades, but his son read it and was inspired by it during the years he was drafting the legislation to create the NPS. This was the origin of the NPS design tradition. This tradition found expression in a group of principles for how national park development should be designed. The 1918 “Lane Letter,” drafted by Steven T. Mather and Horace M. Albright for the signature of Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane, specified that “every activity of the Service is subordinate to the duties imposed upon it to faithfully preserve the parks for posterity.” Their letter indicated how preservation could be achieved while facilitating public access: “In the construction of roads, trails, buildings, and other improvements, particular attention must be devoted always to the harmonizing of these improvements with the landscape. This is a most important item in our program of development and requires the employment of trained engineers who either possess a knowledge of landscape architecture or have a proper appreciation of the esthetic value of park lands. All improvements will be carried out in accordance with a preconceived plan developed with special reference to the preservation of the landscape, and comprehensive plans for future development of the national parks on an adequate scale will be prepared as funds are available for this purpose.”

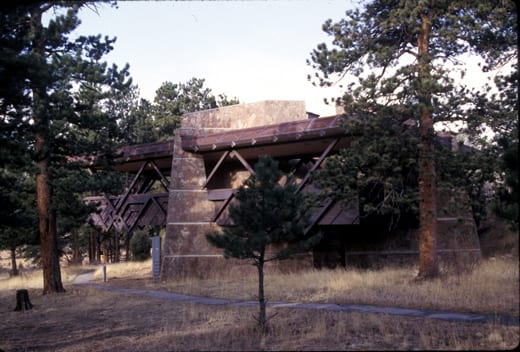

In the 1920s and 1930s, in-house professionals followed this design tradition in creation of “rustic” architecture and “park villages,” and in the “landscape engineering” of park roads that minimized damage to their surroundings. After the war, Mission 66 planners addressed an ever-growing number of cars and people with a revised set of planning principles and Modernist design idioms. But Wirth and his cadre of NPS designers—many of whom were the same individuals who had been responsible for rustic development earlier—held fast to the underlying tradition that guided these updated principles. “Enjoyment without impairment” remained their mantra, and they made frequent reference to earlier NPS policy and practices as they faced postwar levels of use with boldness and creativity. The tradition of NPS design was never a matter of style, but of the ultimate purposes for park development. Mission 66 planners intended to revive that tradition with new approaches to planning and design that would achieve the same goals, under vastly altered circumstances.

By the 1970s, however, neither Congress nor the public seemed to desire further accommodation of automotive tourism in the park system, which at least in some cases had grown to unacceptable dimensions. For many, this meant that the NPS design tradition had run its course. Changes at the agency rightly prioritized natural and cultural resource stewardship over park development, and the roles of scientists and other trained resource managers increased in relevance. This corrective was needed, overdue, and remains fundamental to NPS priorities and mandates today. But it never changed the necessity of park design to help achieve the same purposes of stewardship. For many parks today—from large natural parks to historic sites and battlefields—real improvements in ecological health, resource stewardship, and public experience will not occur without significant change. That change must be planned both to protect park landscapes and to enhance the public’s experience. But the social and environmental contexts of the park system have shifted, once again, and the principles guiding such change require fresh expression. The continuing relevance of the NPS design tradition, in other words, has nothing to do with a return to rustic style, or to Mission 66 Modernism. The tradition defines a set of broad purposes, not a preferred style. Reducing park design to stylistic choices evades the challenges at hand and often perpetuates or worsens the status quo.

In considering the new mission associated with the NPS centennial, officials and their design consultants need to consider how the NPS design tradition can be expressed in new design principles that can guide built form and management policy that address current conditions. Such a revision is very much part of the tradition, and the call for the agency to engage in such a effort is not new. In 1991, the NPS engaged in a system wide review of its policies in recognition of the agency’s seventy-fifth anniversary. Following a conference involving hundreds of participants, six “strategic objectives” were agreed upon and published as the Vail Agenda. The first two objectives effectively restated the general priorities of Olmsted’s 1865 Yosemite Report and the 1916 Organic Act: “Resource Stewardship and Protection,” followed by “Access and Enjoyment.” The document also featured specific recommendations in different categories. Regarding “public use and enjoyment,” the authors proposed that the NPS “embark on an innovative program of facility planning, design, and maintenance” to develop “a new generation of state-of-the-art designs of needed facilities,” while making sure to minimize development within park boundaries and to offer assistance to planning efforts in gateway communities outside park boundaries.

The recommendations of the Vail Agenda remain relevant, and over the last twenty years a number of influences have begun shaping a new iteration of the NPS design tradition. One important direction is indicated by the NPS commitment to the sustainability of its facilities and operations. Sustainable construction materials and technology, for both sites and buildings, represent an important step forward for park projects, as they do for any form of development. But even if a new building is “carbon neutral,” and its parking lot recharges its storm water runoff into the ground on site, these laudable aspects of its design have little to say about whether the building should be there at all, what its program should be, or how its appearance and visual impact will affect its setting.

Such planning for each unit of the park system is required, and all national parks produce General Management Plans (GMPs) that guide official decisions and prioritize actions. The process is structured around the Environmental Impact Statement required by the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act. Typically several alternative futures for a park, each involving somewhat different management directions, are described. Park planners assess the environmental impacts of each, and eventually a preferred alternative is selected. The law mandates a public process, and certainly this is an improvement over how park planning proceeded (almost secretly by today’s standard) under Mission 66. The emphasis on assessing the environmental impacts of policy alternatives, however, make it difficult to use the GMP process to investigate dramatic change, because such actions are likely to have significant impacts on both cultural and natural resources. Anything but the most incremental change is likely to violate NPS environmental or historic preservation policies, if not both. Most GMPs today do not actually describe specific designs for development, or re-development, but are templates for very general resource stewardship goals. Lawsuits from friend and foe alike, in addition to this inherently conservative and limiting planning process, have made it difficult in many cases for individual parks to plan, much less implement, reconfiguration, removal, or relocation of developed areas, or other significant changes in park landscape management policies and practices.

Ambitious (Mission 66-scale) ideas for the redevelopment and reconceptualization of how the public arrives at, moves through, and otherwise experiences its parks, however, are required to address changed contexts and new challenges. The planners and landscape architects attempting to implement alternative transportation systems in national parks have been saying as much for decades. Where they have been successful, such as Zion National Park, we have at least a partial idea of what real change can mean for both park resources and visitor experience. But the difficulties of implementing alternative transportation schemes are as instructive as the few successful examples. Transportation in a park setting is not just a means of getting someplace. As NPS historian Tim Davis notes, moving through landscapes on well designed roads, whether in a carriage or a motor vehicle, has been a primary mode of experiencing and appreciating park landscapes, and an integral part of park design, since at least the eighteenth century. The design of various modes of public circulation was particularly significant in nineteenth-century municipal park design, as at Central Park. If the national park public still clings to the autonomy and experience provided by automobiles, it may not just be out of laziness. Alternative transportation, in many cases, actually implies an alternative national park experience. That alternative experience must be more, not less, inspiring to succeed.

The NPS has also recently sponsored the “Designing the Parks” initiative, which has produced another source of new visions of park design that attempt to address the changes in ecological and cultural conditions we are now experiencing. Through conferences, a student design competition, and its website (designingtheparks.org), the NPS organizers have identified a set of park design principles, and tested them through theoretical projects in seven national parks. Created by groups of students and faculty from a diverse selection of graduate design schools, these projects illustrate how much has changed, at least for this generation of landscape architects, planners, preservationists, and architects. Designing the Parks has been an impressive effort, and one made particularly timely by the fact that in recent years the NPS has steadily divested itself of in-house design professionals. Earlier eras of NPS design were planned and executed mainly by NPS personnel. Collaboration with other agencies, such as the Bureau of Public Roads, and the services of design consultants, especially architects, has always been significant. But only in recent years has the NPS looked to design consultants without its own strong group of in-house professionals to articulate a program of design principles, schematic designs, and specific requirements. Consultants may be very good at providing certain services, but they cannot provide an agency with the reasons, purposes, and guidelines for those services. The Designing the Parks initiative is a very good first step at exploring new ways for the NPS to engage these questions in an era of limited in-house expertise, in which partnerships with universities and non-profit organizations will become even more essential than they already are.

How far can new ideas, such as those students put forward in their Designing the Parks projects, be allowed to go? Put another way, when will NPS planning and design policies and practices catch up with the existing demographic and environmental trends that have altered the situation of every unit of the national park system? In 1916, the NPS itself was created to answer these kinds of questions and to enforce standards and policies across the system from a new and centralized administration. A relatively small group of Mission 66 planners also applied system wide policies and design standards, continuing to assure a minimum level of service and a consistently identifiable look to all national park developed areas. Today, it is apparent that the new iteration of the NPS design tradition taking shape will not be the work of an in-house cadre of designers and officials in Washington; it is evolving through the many partnerships of almost every description that have been forged, especially over the last twenty years, throughout the national park system. With private nonprofit groups, land trusts, and land management agencies at various levels of government, national park managers have already largely re-invented the NPS as a decentralized, partnership-driven organization, facilitating new models of conservation and public engagement. Individually and in groups, the managers of dozens of national parks, historic sites, and recreation areas are actively engaged in devising new, diverse visions for ways in which the public can become more engaged and have more profound experiences of scenic and cultural landscapes.

This is an exciting time, despite (in part because of) reduced federal budgets. But can we say what the new, decentralized iteration of NPS design tradition is, or will be, over the next hundred years? Will there be a systematic consistency of design principles, even within an official culture of decentralized, flexible partnerships that respond to local constituencies, exploit new sources of funding, and benefit from their own political coalitions? This has been and will remain a principal challenge for the NPS as it approaches its centennial. These are vital questions if we believe significant redevelopment—including the removal of facilities in some cases—will be necessary in coming decades for parks and historic sites of all types to continue to fulfill the traditional promise of preservation combined with public enjoyment. Whether the necessity of change is accepted or not, it is ongoing anyway in many units of the park system. Partnerships and entrance fees, as well as regular appropriations, are driving a new era of park development. The dangers of ad hoc and inappropriate development are as real as they were in 1916.

Will the NPS design tradition be successfully redefined as the means of assuring unified policies and the identity of the system? The eventual alternative is, arguably, the effective disbandment of the NPS as a national organization, and the undoing the 1916 legislation even as it is being celebrated. The NPS design tradition remains relevant, but it demands periodic, creative, and system wide reformulation. Park superintendents and their partners, in the best cases (which are too numerous to cite fairly here), are showing the way. But the agency as a whole needs to do more. Whatever one thinks of Mission 66, it left a legacy not only of buildings and developed areas, but of a greatly expanded and diversified park system, an enlarged and professionalized agency staff, and a congressional commitment to the values of national parks. What will the centennial legacy be, after a period of self examination and celebration? Using this anniversary as the catalyst for renewing its bureaucratic identity and purpose, the NPS should re-examine and reconceive its design tradition as the means of perpetuating the vital public purposes of the national park system.

The author would like to thank Rolf Diamant for his comments and advice on this essay.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo name=”ECblog3″ onshow=”Read less…” onhide=”Read more….”]