NAUMKEAG DECONSTRUCTED

It is unnerving to see any garden taken apart, especially one that you have thought, written, and dreamt about as a culmination of history and time–as inevitable, both in the history you have constructed to explain it and in the timeless concept of it you have fashioned in your own imagination.

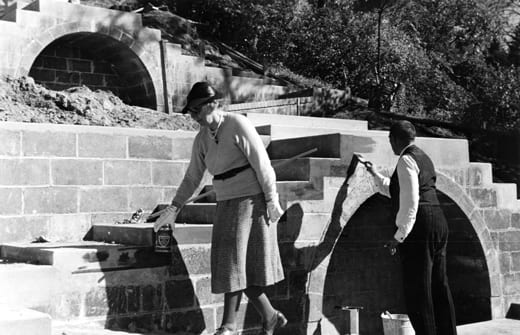

Watching Naumkeag being created (in the 1920s and 30s, via the construction photographs in Fletcher Steele’s archives) was nothing like the scenes I witnessed in Stockbridge last week. Those grainy black-and-white snapshots bespeak an exciting journey into the unknown; the bulldozers and backhoes taking down dying trees and old walls were on the opposite mission. Their purpose was clear, and it was difficult to keep in mind the lofty goal behind the seeming chaos: preservation.

Merriam-Webster’s third definition of preservation, “to keep or save from decomposition,” is the one that most accurately describes what is unfolding at Naumkeag today, the result of a recent $1 million gift and the scholarship that provided the impetus to undertake a dramatic overhaul. I did not provide the anonymous gift, but I did provide the scholarship. It was both thrilling and a bit terrifying to see the money and the ideas working in furious tandem.

I have no question that the intrepid Trustees of Reservations are right to do what they are doing. Fletcher Steele wrote, “The last deep pleasure of the spirit to be learned from a garden will lie in its permanence.” The stewards of Naumkeag are paying attention to what Steele wrote, as well as what he designed.

To survive, the garden needed major work. Water systems were failing, old trees were dying, walls were crumbling. So many details had been lost through shade, attrition, and fading memory that the so-called outdoor rooms were essentially unfurnished. The details had been smudged beyond recognition and the long views had been lost to groves of volunteers. This was not neglect; it was time.

Gardens grow and gardens die. If designs are to live beyond the lives of the plants that structure and enliven them, they need to be taken apart and put back together again. It takes technical expertise, ingenuity, and wisdom to do this well. Wisdom is most important. It is imperative to keep focused on the spirit of the place, and not get lost in the details. That is why we write history as narrative, as opposed to lists of plants or inventories of construction drawings. I have faith in the Trustees that they will bring this perspective to bear on the tasks at hand.

I only wish that I had made one last trip to say good-bye to the garden I knew. The one with the ancient lindens and the encrusted, tottering walls. The new one, in some respects, will be scrubbed behind the ears–younger than I am. None of us will see that old garden again. Not in this lifetime.