FRICK FRACAS: PRESERVATION GROUP FORMS TO SAVE RUSSELL PAGE GARDEN

An ad hoc preservation group, “Unite to Save the Frick,” is organizing to protest a proposed expansion of the Frick Collection, an art museum on Manhattan’s East side, that would destroy the museum’s intimate proportions, alter the visitor experience, and demolish a beloved garden. Known as the 70th Street Garden, the city’s only work by the renowned British landscape architect Russell Page (1906–1985) would be razed, along with a pavilion, according to a June announcement on the Frick’s website.

“When I heard that the Frick planned to destroy the 70th Street Garden and the adjacent one-story Pavilion and replace them with the equivalent of an eleven-story building that would tower over the museum, I was shocked,” says Leslie B. Samuels, a New York City attorney and a member of both the Frick and Unite to Save the Frick. “There must be a better way.” He adds that United to Save the Frick has launched an online petition to spread the word about saving the Page garden, noting that USF supporters include Frick members, architects, landscape architects and historians, design professionals, scholars, and museum visitors from all over the world, as well as residents of New York City.

“LALH is very supportive of efforts to protect this marvelous work of American art, and we will do our best to make others aware of its potential loss,” says Executive Director Robin Karson.

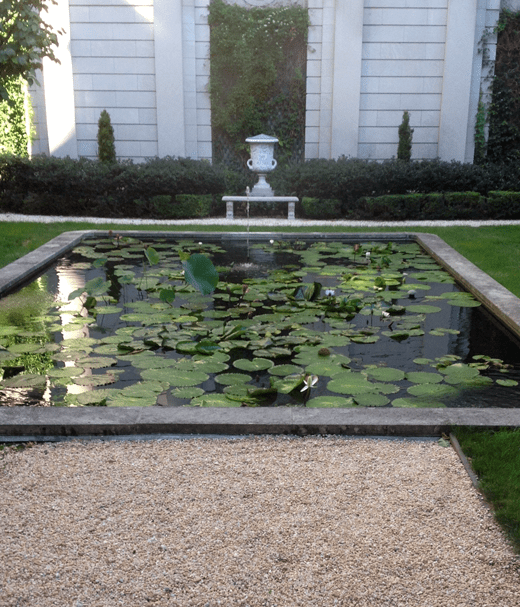

New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman identifies the garden, which Page completed in 1977, as one of the “minor miracles New York manages to shoehorn into small spaces.” Condemning the museum proposal in his July 31 column, Kimmelman captures the garden’s appeal: “Page took time to get the layout right: a rectangular pool, with floating lotus and white lilies in summer, surrounded by pea gravel paths and boxwood. . . . Trees include late-blooming crab apple and Kentucky yellowwood. Page chose clematis and hydrangea to ornament the trellis, wisteria to climb the wall. It’s all a model of precision and proportion, a revelation and breather on the street. . . .”

Beyond its beauty, the garden shares the preservation status of the Frick Collection as a New York City historic landmark, which requires the city’s Landmark Preservation Commission to approve the expansion. If the commission green-lights the plan, the precedent could endanger other landmarks, preservation advocates say. “There is much at stake here—landmark law, architectural integrity, and the notion that a small garden is worthy of preservation,” says Charles D. Warren, a Manhattan-based architect, historian, and co-author of Carrère & Hastings, Architects. Samuels and other members of Unite to Save the Frick share these concerns. The Frick is also a National Historic Landmark, and this designation—the highest recognition of significance conferred by the federal government—could be lost if the Landmark Preservation Commission allows the museum to alter significant features.

Page designed the garden in a small space made available when the 1970s recession forced museum officials to scale down a planned expansion. In announcing the current expansion plan, the Frick’s director, Ian Wardropper, initially said that the museum had intended the garden to be “temporary.” That word vanished from subsequent communications after Charles Birnbaum, FASLA, president of The Cultural Landscape Foundation, reprinted a 1977 Frick press release on his Huffington Post blog confirming that officials at the time intended Page’s garden to be permanent.

Wardropper also minimizes the garden’s importance because visitors are not actually allowed to enter it. “To fill the unused lots adjacent to the pavilion,” he writes, “a small garden was created, which has never been accessible to the public.” Taking issue with the point, Samuels notes that the garden “was always intended to be experienced as a tableau, rather than to be entered.” Karson agrees, pointing out that there are plenty of examples of important viewing gardens, as well as many pocket-sized paintings of great artistic value, including the Vermeers in the Frick’s own collection.

Learn more about the Russell Page Garden by reading the place study.