EASTERN DESIGN IN A WESTERN LANDSCAPE: OLMSTED, RICHARDSON, AND THE AMES MONUMENT

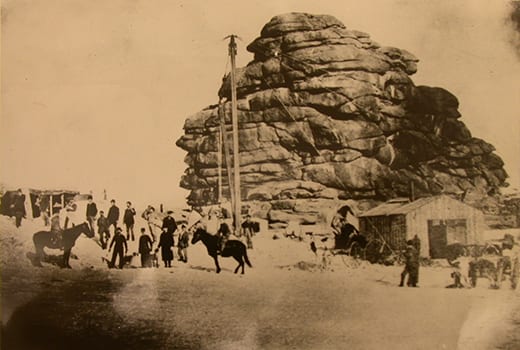

Few people come upon the Ames Monument by chance. Isolated on the high plains, between Laramie and Cheyenne in southeastern Wyoming, the sixty-foot-high pyramid sits on a windswept knoll, eight thousand feet above sea level. Although not far from Interstate 80 (the pyramid is just visible, when driving westward), it defines its own precinct, seemingly remote in time as well as distance. Its enormity is in scale with the vast, treeless landscape of short grass, fantastic granite outcrops, and expansive horizon. The monument’s perfect geometry is in complete harmony with its setting, extending upward in a primordial communion of earth and sky. The combined effect of structure and landscape lends a sense of purpose and pilgrimage to even a casual visit.

Starkly simple, almost atavistic, the monument emanates that rarest quality of built works: a timeless presence. But the structure belongs to a very specific and dramatic moment in both the history of American design and the American West. Built between 1881 and 82, it commemorates the achievements of the brothers Oakes Ames (1804–73) and Oliver Ames (1807–77)—in particular, their role in financing and building the Union Pacific portion of the first transcontinental railroad. The site for the memorial—where the tracks crossed the Laramie Mountains near Evans Pass on their way to meet the Central Pacific Railroad in northern Utah—was chosen by the Union Pacific directors because it was then the highest point of their line.1 In 1879 they commissioned the forty-one-year-old architect Henry Hobson Richardson to design a monument memorializing the Ames brothers, who had been principal investors and directors of the corporation.

Richardson responded with an idea for a memorial unlike any that had been produced in the United States: a massive, slightly stepped pyramid, sixty-foot square at its base, rising to a sixty-foot height, constructed of rusticated granite blocks quarried from a nearby outcrop. The architect had never visited the remote location (although he saw his work before he died). Yet site and monument were perfectly matched, enhancing one another. Richardson’s close friend and collaborator, the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, observed in 1887 that he “never saw a monument so well befitting its situation, or, a situation so well befitting the special character of a particular monument.”2

Olmsted had reason to be particularly interested in the Ames Monument. In the early 1880s he and Richardson were working together on a number of projects in Massachusetts, notably for the extended Ames family in North Easton. The Ames Shovel Works, established before the American Revolution, had grown into a major manufacturing center there, and Oakes and Oliver Ames oversaw an empire of manufacturing and finance. In 1863 Oakes helped organize the Republican Party in Massachusetts and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. There he became a member of the select committee responsible for the Pacific Railway Act of 1864. Oakes and Oliver Ames, among others, were recruited to buy stock in the new Union Pacific corporation—a scheme that was probably framed as both sound investment and a patriotic duty. As a result of their investments—and the complicated and sometimes nefarious deals made in Congress around the fluctuating prices of railroad corporation stock—Oakes became a central figure in one of the most notorious political scandals of the day, the Credit Mobilier affair, named for a Union Pacific subsidiary construction company.3 He was censured in Congress in 1872 and died the next year.

The family, intent on clearing the Ames name, sponsored a series of public works in North Easton. Olmsted and Richardson collaborated on a public library, dedicated to Oliver, and a “memorial town hall,” dedicated to Oakes, as well as other Ames family commissions in the area. For their part, the directors of the Union Pacific committed to the creation of a monument dedicated to the two brothers, sited at what was then the station stop of Sherman, Wyoming.

Although Olmsted was probably not directly involved in the design of the monument, we know that he discussed Richardson’s conceptual sketch with the architect and saw the finished result. Shortly after Richardson’s premature death, in 1886, Olmsted referred to it in a letter as “our monument.” The prior decade had been a period of maximum mutual influence between the two designers, who at the time were the country’s leading figures in their respective fields. In an article published several years later by their mutual friend, the art critic (and Richardson biographer) Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer, she provided insight into the extent of the collaboration between the two friends, who were also neighbors in Brookline, Massachusetts. Richardson “was constantly turning to Mr. Olmsted for advice, even in those cases where it seemed as though it could have little practical bearing upon his design. And where it could have more conspicuous bearing he worked with him as a brother-artist of equal rank and of equal rights with himself. The Town Hall at North Easton may be cited as one example of the extraordinary success which can spring from such co-operation, and Mr. Richardson was never tired of explaining how invaluable in this case had been Mr. Olmsted’s assistance.”4

The commissions in North Easton give the best indication of how Olmsted’s ideas of site-based design effected a transformation in Richardson’s architecture. The memorial town hall was sited just west of the memorial library, creating a new and better-defined town center. Together the two men created a work of civic art responsive to the site and especially to local geology, advancing our understanding of how landscape and architectural design can be melded. In her critical assessment of the town hall, Van Rensselaer focused on how Richardson used the rocky location to advantage, and how Olmsted extended and enhanced this method. She described the approach to the building as “a series of successive platforms and short flights of steps, kept duly inconspicuous and artistically adapted to the inequalities of the rocky surface.” She was particularly enamored of the use of the depressions in the land and the site’s granite formations as design elements and “the manner in which the tower of the hall rises out of the rock, almost like a natural development.”5 It appears as if the rock is part of the building and the building part of the rock.

As he did elsewhere, Olmsted designed the landscape setting for Richardson’s buildings in part by exposing and emphasizing the rocky surface of the site. Directly opposite the town hall, he created a massive boulder terrace, on which a stone cairn commemorated the town’s Civil War dead. The joints of the boulder masonry of the terrace were filled with soil to support vines and other plants. An arched opening allowed passage through it, and steps were incorporated into its stones. At the F. L. Ames estate nearby, Richardson created a memorable gatehouse that also employed boulder masonry, and the building itself served as an arched entryway into estate grounds designed by Olmsted. Like the design of the Ames Monument, the North Easton collaborations during this period demonstrate the continuity between Olmsted’s structured landscapes and Richardson’s landscape-inspired structures, each rooted in an enhanced sense of the site’s geology.

While he was working in North Easton, Olmsted was simultaneously designing the Back Bay Fens in Boston, a public park evoking the estuarine wetland that formerly existed there. In 1880 he asked Richardson to collaborate by designing the Boylston Street Bridge. Built in irregular granite ashlar (although Olmsted originally wanted more rugged boulder masonry), the undulating, unornamented mass of the bridge suggested an organic form consistent with Olmsted’s landscape. Both designs eschewed historical references, and were inspired instead by the formal character and geology of the site. The architectural historian James F. O’Gorman has described the bridge as a “complete collaboration between architect and landscape architect, between man and nature, between architecture and geology.” The same is true, O’Gorman observed, “of the man-made mountain Richardson designed at this time in memory of Oakes and Oliver Ames out in Sherman, Wyoming, a monument conceived as a conventionalized outcropping and quarried from a real one.”6 The development of this design aesthetic, employing highly engineered and articulated structures that were nevertheless evocative of natural features, would mark a turning point in Richardson’s career—and, considering his influence on Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, in the course of American design history.

For the Wyoming commission, Richardson, who had never traveled to the West, could draw on the wealth of photographs, engravings, and paintings of western landscapes that had recently become widely available to the public—in part thanks to of the transcontinental railroad. More important to his conception and approach was input from Olmsted, who, unlike Richardson’s other colleagues in Brookline, had lived in the West. In the 1860s, while managing the Mariposa Mine in California, Olmsted had given considerable time and thought to landscape design in semiarid regions. In 1865 he wrote an influential report recommending management policies for the preservation of Yosemite Valley, where he met and employed the geologist Clarence King. During the 1880s, he crisscrossed the country to work on a number of commissions—most notably a project for Stanford University—in which he developed a distinctive approach to landscape design appropriate to the formal character and climate of the region.

In 1881, the Norcross Brothers, a construction firm that realized many of Richardson’s designs in the East, traveled west to work on the Ames Monument. The company oversaw a labor camp on the site for two years, until the commission was completed. Men, tools, and supplies were brought in, of course, by the Union Pacific. There is no evidence that Richardson visited the site of the monument either before conceiving its design or during its construction. However, Frederick Lothrop Ames, who acted as the family representative for the North Easton commissions, suggests in a letter that the architect traveled with him to Sherman in the family’s private car in September 1883, after the project was complete. Unfortunately, Ames makes no mention of the monument itself.

Four years later, however, Frederick Law Olmsted was passing through and requested a five-minute stop at Sherman to assess its condition. On January 29, 1887, Olmsted wrote to F. L. Ames, again speaking of the monument in proprietary terms:

I had several times heard that our monument had been much injured by the dinting of pebbles thrown against it in heavy gusts of wind and having been told by one of the officials of the U. P. that he believed the reports were true with his assistance I obtained an order to have the train detained five minutes this morning so that I could have a look at it. The surface of the ground in the neighborhood, as you will remember, is largely composed of flakes of granite from half an inch to an inch in diameter; there was a high wind blowing and I could believe that if a little intensified, a man might get a very unpleasant pelting, but the granite fragments are thin, scaley and brittle and it seemed to me that it would take countless blows of them to make any notable impression on a firm granite wall. I could take but a moment’s passing glance at the monument and in this could not see that the slightest impression had been made upon it. And what is likely to be made in the next thousand years will, I should think, no more than improve it.

As this reference to “our monument” suggests, Olmsted saw himself as at least influencing the design. He goes on to relate, “A gentle man tells me that he has often passed it but seeing it only from a distance it had never occurred to him that it was anything other than a natural object. Yet when it can be seen from the train at the Station, as it could not this morning, and I am afraid, seldom can, it has much more fine finished stateliness than was to have been readily imagined from Richardson’s drawing.”7 Olmsted had conceived of the structure as more rugged and unrefined—perhaps due to the thick lines and bold form of Richardson’s original sketch, which does not survive. In seeing the structure up close, he was struck by its fine craftsmanship and the clean articulation of the rusticated and partially randomized ashlar courses. This craftsmanship was typical of the Norcross Brothers. From afar the masterful finish evoked the surrounding granite outcrops, which were eroded into weird formations. But on close examination, the work was impeccably refined.

In his biography of Richardson, Henry-Russell Hitchcock celebrated the Ames Monument, which exuded the power of “a great glacial moraine roofed and made habitable.” Hitchcock was no geologist, as his allusion makes clear. But writing at the height of the modern movement, the critic claimed the pyramid as a work looking beyond its own time for something timeless; he saw Richardson “seeking his inspiration back in the time before architecture took form.” The monument was perhaps the purest expression of the new, distinctively American and modern approach to architectural design that Richardson developed toward the end of his life, after working with Olmsted. Hitchcock judged it to be “perhaps the finest memorial in America.”8

Historians since have not only agreed, but have analyzed the Ames Monument as a critical moment in architectural history. Mark Wright identifies it as “the fulcrum on which Richardson’s work pivots—before and after” and suggests that the architect’s “imaginative confrontation with the harsh landscapes of the Western United States” resulted in a “new primitivism” reflected in his successive buildings.9 The formal characteristics that identify Richardson’s later buildings—simplicity, mass, rich surface detail—were expressed in Wyoming more freely and independent of any style, even his own version of the Romanesque. Subsequently Richardson produced some of his greatest works, including the Crane and Billings libraries, the Robert Treat Paine House, and the Marshall Field Wholesale Store. His experience of designing the Ames Monument and his collaboration with Frederick Law Olmsted played a role in their success.

Today, the monument remains in very good condition. As Olmsted predicted, the severe weather conditions of southeastern Wyoming, far from deteriorating its surfaces, “no more than improve it.”10 The most serious damage has been due not to weather but vandalism. In the 1980s, the two portrait relief panels of Oakes and Oliver Ames, by the greatest American sculptor of the era, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, were damaged by rifle fire. Someone who was apparently an expert shot (it is Wyoming) hit them both squarely in the nose, despite the fact that the reliefs are set into the monument about fifty feet off the ground. Nevertheless, for those who come upon the Ames Monument today, only a short drive on an unpaved road from Interstate 80, its power and its almost sacred precinct endure. Much of that effect is due to its remarkable setting in the treeless high plains, in a regional landscape that has altered little over millennia. Over one hundred years ago, eastern design met western landscape and, in telling part of the story of the transcontinental railroad, created a truly timeless expression of American culture.

Ethan Carr, FASLA

Professor, University of Massachusetts

Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning

Ethan Carr’s essay originally appeared in Site/Lines, the journal of the Foundation for Landscape Studies.

All photos courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

ENDNOTES

1. The route of the Union Pacific was shifted about three miles to the south in 1901, so that only the graded earth marking the original route remains. H. R. Dieterich Jr., “The Architecture of H. H. Richardson in Wyoming: A New Look at the Ames Monument,” Annals of Wyoming 38, no. 1 (April 1966): 49–53.

2. Frederick Law Olmsted to Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, February 6, 1887, Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, LOC.

3. Winthrop Ames, The Ames Family of Easton, Massachusetts ([North Easton, MA], 1938), 145; Maury Klein, Union Pacific (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 1:79, 91, 97.

4. Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer, “Landscape Gardening III,” American Architect and Building News 23 (Jan. 7, 1888): 3–5.

5. Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer, Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works (Boston, 1888; repr., New York: Dover, 1969), 71.

6. James F. O’Gorman, Living Architecture: A Biography of H. H. Richardson (New York: Simon & Schuster Editions, 1997), 133.

7. Frederick Law Olmsted to Mr. Ames, U.P. R.R. near Sherman, January 29, 1887, Ames Family Papers, Stonehill College. Olmsted wrote a letter to Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer with a similar description of his examination of the monument. He adds: “Within a few miles there are several conical horns of the same granite projecting above the smooth surface of the hills. It is a most tempestuous place and I have no doubt that at times the monument is under a hot fire of little missiles, but they will only improve it, I think (I may be mistaken. I could only glance at it; there was some snow upon it and the wind and cold so horrible that my eyes were half drowned.” Frederick Law Olmsted to Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, February 6, 1887, LOC. Van Rensselaer quotes a significant portion of this letter in her biography, Henry Hobson Richardson, 72.

8. Henry-Russell Hitchcock, The Architecture of H. H. Richardson and His Times (1936; repr., Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1970), 197, 202–3.

9. Mark Wright, “H. H. Richardson’s House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 68 (March 2009): 80, 82.

10. Frederick Law Olmsted to Mr. Ames, U.P. R.R. near Sherman, January 29, 1887, Ames Family Papers, Stonehill College.