Charles E. Beveridge, Alexandria, Virginia (2015)

Charles E. Beveridge has been studying and writing about Frederick Law Olmsted’s career for more than five decades—for thirty-five years as series editor of The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. As a scholar and preservationist, Charlie is the most important individual explaining and defending the significance of Olmsted’s legacy in our time. His remarkably rich career has led to a broader popular as well as scholarly understanding of Olmsted’s many contributions to American life, in the twenty-first century as well as the nineteenth and twentieth. For his many accomplishments Charlie was elected an honorary member of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 2005 and the following year received its Frederick Law Olmsted medal for “environmental leadership, vision, and stewardship.”

Charlie was born in Boston on May 17, 1935. He grew up on the Maine coast in an 1850s farmhouse his great-grandfather had built and his parents restored. Eliot Beveridge, a painter devoted to the landscapes and seascapes of coastal Maine, surely influenced his son in important ways, as did the rugged coast and North Haven Island, which remains Charlie’s spiritual home. After attending the Putney School, then Harvard College (class of 1956), from which he graduated magna cum laude, Charlie pursued graduate study in history under William Best Hessseltine at the University of Wisconsin, where he earned his PhD in 1966.

While still a graduate student, Charlie moved to Washington, D.C., in 1963, to work in the Olmsted Papers. He taught social history at the University of Maryland beginning in 1964, but in 1973 joined the staff of the Olmsted Papers Project, which Charles C. McLaughlin had begun with his doctoral dissertation in 1960. In 1972, the sesquicentennial of Olmsted’s birth, the Olmsted Papers Project took off, and McLaughlin hired Charlie and Victoria Post Ranney as associate editors. Charlie continued teaching, though, through one-on-one conversations with younger scholars and in public lectures, interviews, appearances in films devoted to Olmsted’s life and works, and other venues that enabled him to reach a broad audience.

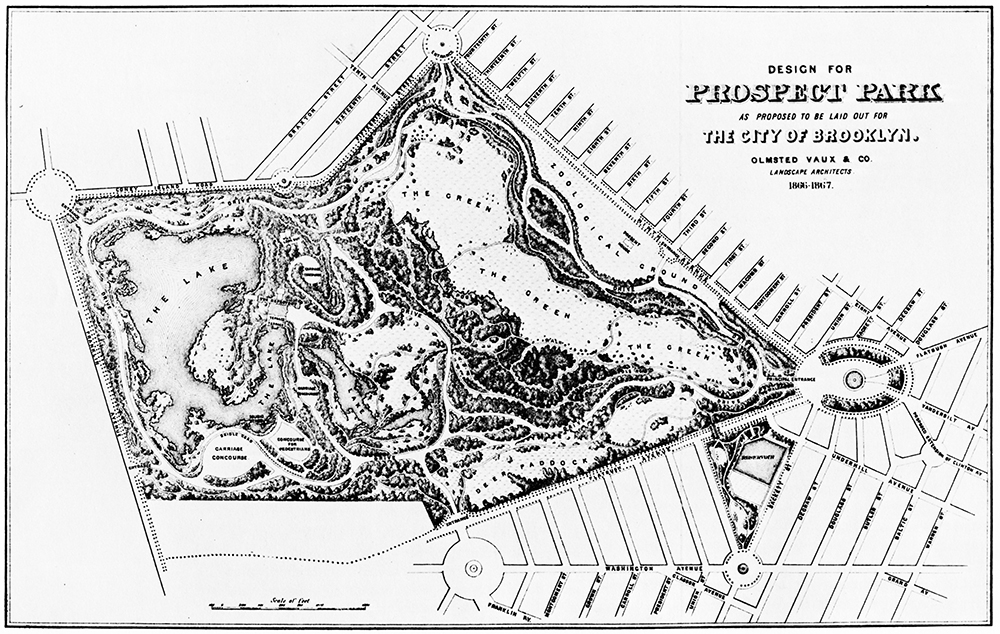

As the series editor of the Olmsted Papers since 1980, Charlie has pushed the project forward when funding was uncertain and worked with a number of volume editors as well as a succession of graduate research assistants. If I could summarize Charlie’s leadership approach simply, I would single out his remarkable patience and absolute determination that we do our best work. In writing annotations for one of the last documents in volume nine, The Last Great Projects, 1890–1895 (2015), in which Olmsted criticizes the nomenclature of streets, specifically mentioning the “Sackett Street Parkway Boulevard,” I must have written an innocuous note identifying Sackett Street in Brooklyn that missed the essential point. Charlie reminded me that the course of Eastern Parkway followed Sackett Street as it proceeded east from Prospect Park and Grant Army Plaza, and that Olmsted was arguing for precision in the language of street naming just as he was for precision in landscape design. Over the last few years, Charlie has been working on Frederick Law Olmsted: Plans and Views of Public Parks, a comprehensive collection of images published by Johns Hopkins University Press. A second illustrative volume will follow, the final in the Olmsted Papers series. After its completion, Charlie will edit a one-volume compilation of Olmsted’s writings for the Library of America.

In addition to his work as a scholar and editor, Charlie has been passionately involved in promoting the preservation of Olmsted landscapes. He was one of the founders of the National Association for Olmsted Parks and has served as historian or consultant for the restoration of Olmsted parks in Boston, Chicago, Rochester, New York, Louisville, Kentucky, Atlanta, and New York City, among other places. He was also senior consultant for the Massachusetts Olmsted Historic Landscape Preservation Program; prepared a master plan for the preservation of the landscape Olmsted designed at Riverside, Illinois; advised on the preservation of the U.S. Capitol grounds; and helped plan the centennial celebrations of the preservation of the Yosemite Valley and the New York State Reservation at Niagara. In all of these capacities—scholar, mentor, advocate, preservationist—Charlie has become the voice speaking for Olmsted and the enduring significance of the public parks that are his greatest legacy.

—David Schuyler is Arthur and Katherine Shadek Professor of the Humanities and American Studies at Franklin & Marshall College and author of Apostle of Taste.