Arete Warren, New York City (2023)

Arete Warren’s country house in the Berkshire Hills of northwest Connecticut is known as “ulubrae”—a name her husband took from Horace, translating it as “house in the sticks.” (The lowercase is intentional.) And that’s the feeling of this place, especially after the drive up from New York City. The central core of the house was a lively tavern in the mid-eighteenth century, and through its restoration, the Warrens preserved its historic beams and salvageable wood, and an ambience appropriate to a house devoted to books. Together, ulubrae and Warren’s home in Manhattan, where her rare books reside, represent the breadth of her interests. She is a member of the Millbrook Garden Club (a member club of the Garden Club of America) and the Grolier Club of New York City, the country’s oldest society for bibliophiles, along with more than a dozen other associations and boards related to education, philanthropy, and historic preservation. To every endeavor and every meeting, Warren brings the perspective of a historian who understands the value of cultural aesthetics. For more than fifty years, she has forged new paths in historic preservation, pushing committees to make the right choices and put their funds in the right places to preserve worthy landscapes, buildings, and works of art.

Born in Chicago, Warren grew up in a rural Illinois town a hundred and fifty miles south of the city. Her father was an independent landowner, as were centuries of her family before him. All the successful farmers in town were also professionals—her father was a banker—and lived near the three blocks that comprised Main Street. Growing up, she was well aware of the cattle industry’s role in the national economy and the significance of the railroad as a lifeline for the distribution of goods. Along with the farms, a sense of personal responsibility became part of Warren’s inheritance. From her father, she gained a respect for architecture, and from her mother, a voracious appetite for books.

In 1968, Warren matriculated at Northwestern University, entering as a math major but soon deciding on history as her focus. A course in art appreciation fostered her growing interest in the arts. Before graduation, one of her professors suggested she contact Barbara Wriston, director of museum education at the Art Institute of Chicago, to inquire about a career in museum work. Wriston explained what was needed: a graduate degree in art history; international travel to see masterpieces in person; and work in a museum abroad. Undaunted by the list of prerequisites, Warren earned a master’s at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; visited as many national and international art museums as possible; and was awarded an internship at the prestigious Victoria and Albert Museum.

Throughout her time at the V&A, Warren was encouraged by its director, the renowned art historian John Pope-Hennessy. Her internship was extended, and over the next two and a half years, she gained valuable teaching experience giving public lectures to students and general audiences. Working in the circulation department provided a hands-on education in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art, as well as an introduction to mounting and managing traveling exhibitions. When she left the V&A in 1973, Warren took with her an elite education in art history, specialized training in exhibition design, and a sophisticated aesthetic sensibility.

Returning to New York, she was hired as education and program coordinator for the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts and Design. After a year, however, she was selected by Britain’s National Trust to establish a U.S. fundraising arm in New York City. As founding executive director of the Royal Oak Foundation, Warren sought to expand the National Trust’s base of American members dedicated to funding preservation projects in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. After working out of her apartment for five months, she moved the operation to the brownstone that also housed the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, the Central Park Conservancy, and United World Colleges. The historic building had special meaning for Warren after she learned it had been the former home of Clara Woolie Mayer, an influential liberal thinker and major force behind the development of the New School for Social Research.

Inspired by her new mission, Warren strove to build the Royal Oak Foundation with a distinguished board of directors and attract members through its programming—first-rate lecture series, national conferences, tours, and scholarships. It was through her experience with the National Trust that Warren began to comprehend the international importance of preservation. Whether it concerned the White Cliffs of Dover or Knole estate in West Kent, the discussion involved history and culture, in addition to scenic beauty. Under her leadership, the Trust gained both the significant financial boost it sought from American supporters and a valuable network that continues to enrich the cultural landscapes of both countries. Later Warren would build on this partnership as U.S. chair and trustee of the American Museum in Britain.

After eight years leading the Royal Oak Foundation, Warren received a call from Joseph Curtis Sloane, retired professor and chair of the UNC Department of Art and Art History and trustee of the North Carolina Museum of Art, the first state art museum in the country. Relocating to Raleigh, she began her job as assistant to the director working with the director and with the state department of cultural affairs to establish the museum’s presence in its new location outside the beltline. (The museum’s new building was designed by Edward Durrell Stone.) Her achievements at NCMA further confirmed Warren’s reputation as a facilitator who successfully established educational programs for major cultural institutions.

In 1985 she married William Bradford Warren, a lawyer who shared her interest in book collecting and historic preservation. The couple made their home in a 1929 apartment building designed by Charles Platt on the Upper East Side. She resigned from her museum job but soon acquired a new project: co-authoring Glass Houses: A History of Greenhouses, Orangeries, and Conservatories. Warren’s friend and colleague May Woods had completed the English side of the history, but Rizzoli, her publisher, wanted to add the American side. Research took Warren throughout the country—to early greenhouses at Mount Airy Plantation in Richmond County, Virginia, and Wye House, near Easton, Maryland, as well as the Conservatory of Flowers in Golden Gate Park and the contemporary Lucile Halsell Conservatory at the San Antonio Botanical Garden. Her archival research led to the discovery of late eighteenth-century greenhouses, correcting the idea that American glass houses were a product of the mid-nineteenth century and expanding the scope of their influence. The book required illustrations, and Warren responded by learning to use a camera.

Her scholarship on glass houses led to an invitation to lecture at Vassar College for the Millbrook Garden Club, which six months later she was invited to join and serve on its Garden History and Design Committee. As Warren explains, she approached gardens from an architectural point of view, by uncovering their “bones.” Over time, plants change—gardeners are forever putting in and pulling out—but hardscape remains. She soon realized the myriad ways her training as an art historian and her museum work could enhance the GCA’s educational mission.

In 1995, Warren was appointed to the City of New York Mayor’s Commission for Protocol, an experience that led to powerful connections and inside knowledge of city politics essential for a champion of historic preservation. She subsequently served on the New York State Board for Historic Preservation and the Empire State Plaza Art Commission. A member of the Preservation League of New York State since 1974, she has served as chair and currently sits on its Trustee Council. Warren’s work has earned her awards from the Preservation League and the Friends of the Upper East Side.

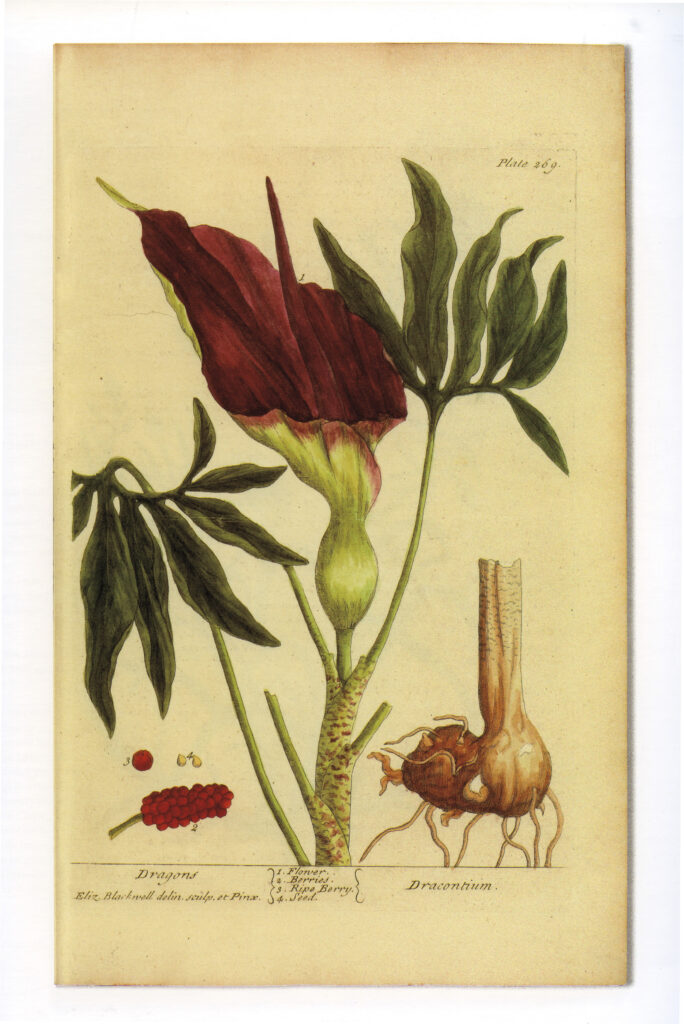

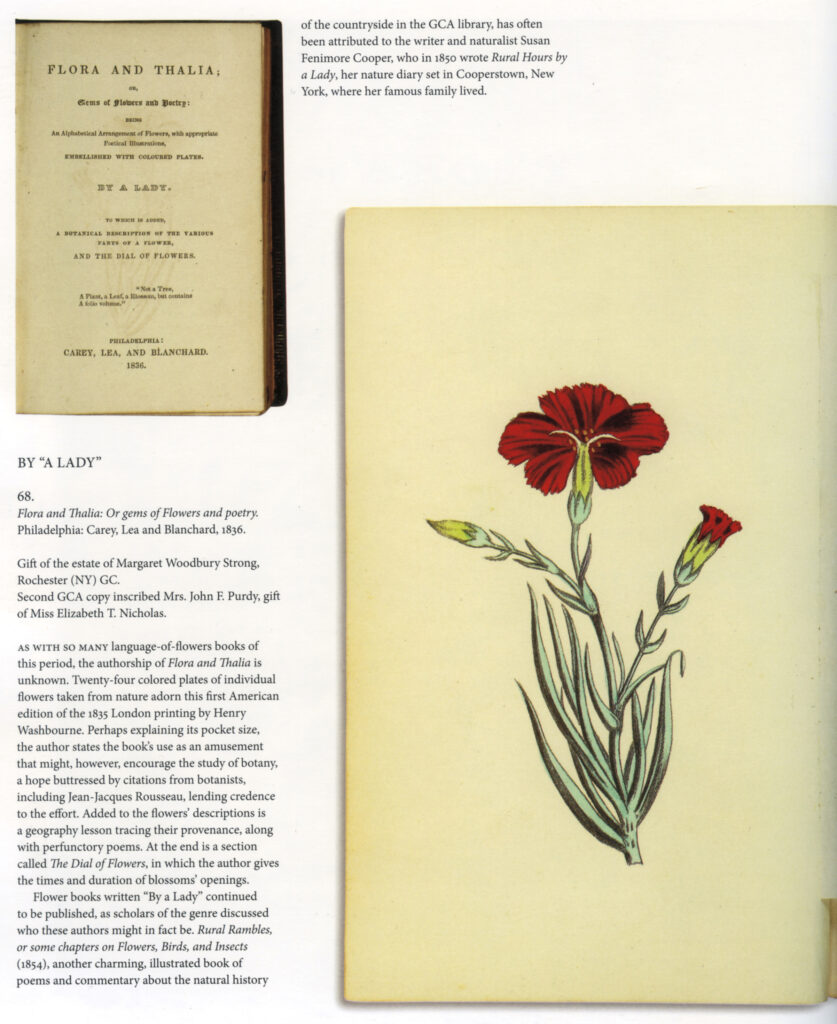

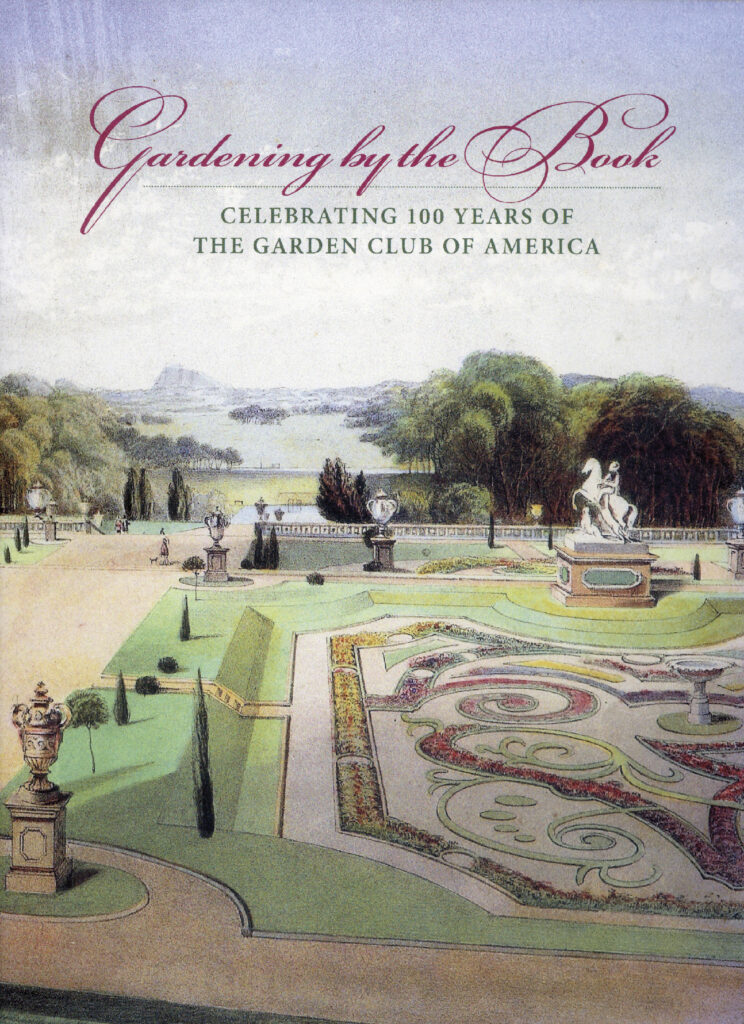

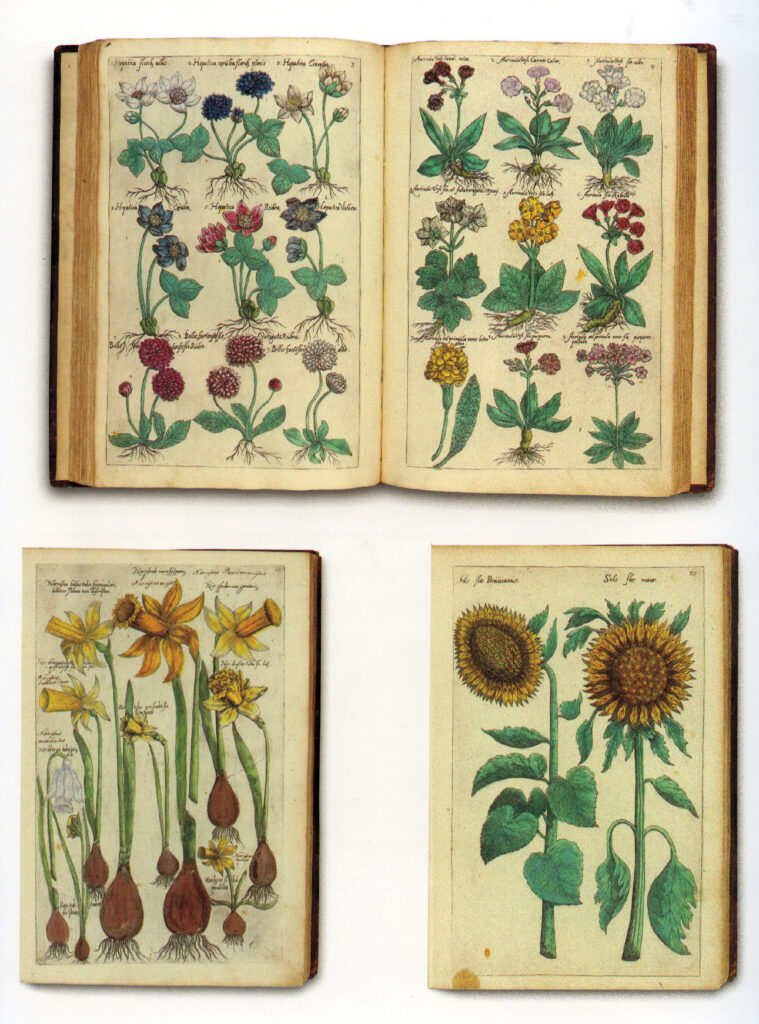

During this time, her activity in the GCA extended to leadership positions, first as New York zone representative and subsequently as vice chair and chair of its Garden History and Design Committee. As chair of the Library Committee when the GCA began planning its centenary celebration, Warren proposed an exhibition of rare books in the GCA’s remarkable collection to be held in 2013 at the Grolier Club in New York. The collaboration would recognize the confluence of the GCA’s mission—“to stimulate the knowledge and love of gardening”—and the Grolier’s, “to foster the study, collecting, appreciation, and celebration of books.” Warren spent the next three years researching, curating, and writing the catalog for Gardening by the Book: Celebrating 100 Years of the Garden Club of America. The exhibition comprised four centuries of international treasures, from early seventeenth-century botanical texts to an album of Flower Stamps from All the World created in 1973. In her introductory essay to the catalog, Warren traces the origins of the GCA through its book acquisitions (spurred in the early 1930s by Mabel Choate, then chair of the Library Committee), exhibitions, and publications and deftly illustrates the importance of books in the lives of prominent landscape architects, including early contributors to the GCA Bulletin Beatrix Farrand, Martha Brookes Hutcheson, and Fletcher Steele.

Warren was a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy in Rome in 2014, and in 2016 she received the GCA’s National Achievement Medal “in recognition of an inspiring visionary, whose erudition, formidable energy, and perseverance stimulate the love and knowledge of books and gardening.”

Over the last several years, Warren has advocated for a wide range of projects as an adviser to the Gerry Charitable Trust and a co-trustee of the Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Foundation, and as an adviser to the Jay Heritage Center in Rye, New York, she has helped guide the restoration of its historic gardens. A member of the board of directors for The Hudson Review, Warren also served for more than a decade on the Council of Fellows of the Pierpont Morgan Library. Arete Swartz Warren is a “cultural activist” with a gift for motivating people to support preservation and the humanities. In her spare time, she takes pleasure in the art and literature that are so much a part of her work.